This object, or the text that describes it, is deemed offensive and discriminatory. We are committed to improving our records, and work is ongoing.

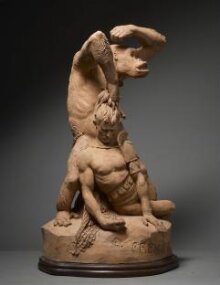

Gorilla defeating a Gladiator

Sculptural Group

1876

1876

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This terracotta is one of the most deeply unsettling and visually arresting sculptures exhibited in mid-19th-century Europe. It shows not only Emmanuel Frémiet’s talent as a sculptor in clay, but to have been deeply engaged in contemporary issues and debates.

Frémiet was a leading sculptor of small-scale animals, soldiers and equestrian figures, but also of a group of dramatic sculptures of animals in violent combat with human beings, epitomised by this recently re-discovered example. In 1840 he entered the studio of Jacques-Christophe Werner, lithographer and principal painter at the Musée National d’histoire naturelle in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris. Here he studied anatomy and drew studies of animals from life, later succeeding Antoine-Louis Barye as Professor of Drawing. He was influenced by Barye, famous for his animal sculptures, and also by François Rude, under whom he studied sculpture.

At the 1850 Paris Salon Frémiet exhibited a small bronze, Hound licking his wound’ (V&A, 256-1896), which firmly established him as a talented ‘animalier’ sculptor of small-scale works. However, at the same Salon he exhibited a much larger plaster sculpture, Wounded Bear (also titled Bear and Gladiator), the first of his group of works depicting men in aggressive combat with beasts. These ‘combat’ works feature animals modelled with striking verisimilitude, but the focus is on the interaction between man and beast at the culmination of violent and deadly encounter. At the 1859 Salon the jury had rejected Frémiet’s first ‘Gorilla’ sculpture, the Gorilla carrying off a Negress, although this was partially reprieved by the Comte de Nieuwekerke and displayed behind a curtain at the entrance to the Salon.

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection (1859) as well as Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861), describing gorillas, would have been known to Frémiet at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Tales of this ferocious, human-like animal in areas of Africa new to Europeans prompted a scramble to acquire gorillas and gorilla parts for collections. The gorilla was central to debates about the place of humans within the order of primates, and Frémiet later recalled, “At a time when a lot of noise was starting to be made about mankind and apes being brothers, it was certainly audacious; and my work proved even more aggravating since, the gorilla being the ugliest of all the primates, the comparison was hardly flattering for humans.” Those debates were still raging when Frémiet made this terracotta in 1876.

The sculpture draws upon Frémiet’s direct observation and recording of gorilla specimens at the Natural History Museum in Paris. It is masterly in its execution, the clay partly cast and the surface vigorously tooled to convey the texture of the gorilla’s fur, the gladiator’s hair, net and other accessories. The gladiator is specifically a Retiarius, a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment inspired by that of a fisherman, and he is academically and correctly depicted with only a shoulder guard, net and trident. The composition has the drama of Baroque precedents and in its depiction of Gladiators in combat parallels the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Above all, it encapsulates in visual form the raging debates in the mid-19th century about the supremacy (or not) of humans, international explorations of Africa, and research into the natural world. It is a purposefully arresting work which still shocks today, as it did at the Salon of 1876.

Frémiet was a leading sculptor of small-scale animals, soldiers and equestrian figures, but also of a group of dramatic sculptures of animals in violent combat with human beings, epitomised by this recently re-discovered example. In 1840 he entered the studio of Jacques-Christophe Werner, lithographer and principal painter at the Musée National d’histoire naturelle in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris. Here he studied anatomy and drew studies of animals from life, later succeeding Antoine-Louis Barye as Professor of Drawing. He was influenced by Barye, famous for his animal sculptures, and also by François Rude, under whom he studied sculpture.

At the 1850 Paris Salon Frémiet exhibited a small bronze, Hound licking his wound’ (V&A, 256-1896), which firmly established him as a talented ‘animalier’ sculptor of small-scale works. However, at the same Salon he exhibited a much larger plaster sculpture, Wounded Bear (also titled Bear and Gladiator), the first of his group of works depicting men in aggressive combat with beasts. These ‘combat’ works feature animals modelled with striking verisimilitude, but the focus is on the interaction between man and beast at the culmination of violent and deadly encounter. At the 1859 Salon the jury had rejected Frémiet’s first ‘Gorilla’ sculpture, the Gorilla carrying off a Negress, although this was partially reprieved by the Comte de Nieuwekerke and displayed behind a curtain at the entrance to the Salon.

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection (1859) as well as Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861), describing gorillas, would have been known to Frémiet at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Tales of this ferocious, human-like animal in areas of Africa new to Europeans prompted a scramble to acquire gorillas and gorilla parts for collections. The gorilla was central to debates about the place of humans within the order of primates, and Frémiet later recalled, “At a time when a lot of noise was starting to be made about mankind and apes being brothers, it was certainly audacious; and my work proved even more aggravating since, the gorilla being the ugliest of all the primates, the comparison was hardly flattering for humans.” Those debates were still raging when Frémiet made this terracotta in 1876.

The sculpture draws upon Frémiet’s direct observation and recording of gorilla specimens at the Natural History Museum in Paris. It is masterly in its execution, the clay partly cast and the surface vigorously tooled to convey the texture of the gorilla’s fur, the gladiator’s hair, net and other accessories. The gladiator is specifically a Retiarius, a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment inspired by that of a fisherman, and he is academically and correctly depicted with only a shoulder guard, net and trident. The composition has the drama of Baroque precedents and in its depiction of Gladiators in combat parallels the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Above all, it encapsulates in visual form the raging debates in the mid-19th century about the supremacy (or not) of humans, international explorations of Africa, and research into the natural world. It is a purposefully arresting work which still shocks today, as it did at the Salon of 1876.

Object details

| Object type | |

| Title | Gorilla defeating a Gladiator (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | terracotta, cast and modelled |

| Brief description | Terracotta sculpture of a Gorilla defeating a gladiator, signed E. Fremiet, French, 1876 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label | Gorilla defeating a Gladiator (‘Rétiaire et Gorille’) / Emmanuel Frémiet (1824–1910) / 1876

This is one of the most deeply unsettling and visually arresting sculptures exhibited in Europe in the 19th century. Frémiet was a skilled sculptor first known for his careful observations of animals. Later, he produced larger groups like this, capturing dramatic combats between man and beast. These shocked viewers because they showed the animal as victorious, breaking with previously established sculptural traditions.

Frémiet’s depiction of a gorilla triumphant over a human had a particular impact and resonance at this time. Europeans had only discovered gorillas in about 1850 and were fascinated by them. In 1871, Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man had spelled out the shared ancestry of humans and modern apes. Darwin and others sparked vigorous contemporary debates about the place of humans in the natural world order.

This is the first acquisition supported by V&A Members to be featured in the Members’ Reception Area.

Paris, France / Terracotta, cast and modelled(February 2018) |

| Credit line | Purchased with support from V&A Members, and the Captain H.B. Murray and Dr W.L. Hildburgh bequests |

| Object history | NB The term "negress" was used historically to describe people of black African heritage but, since the 1960s, has fallen from usage and, increasingly, is considered offensive. The term is repeated here in its original historical context. The terracotta was exhibited at the Salon in Paris, 1876 (no. 3287) |

| Summary | This terracotta is one of the most deeply unsettling and visually arresting sculptures exhibited in mid-19th-century Europe. It shows not only Emmanuel Frémiet’s talent as a sculptor in clay, but to have been deeply engaged in contemporary issues and debates. Frémiet was a leading sculptor of small-scale animals, soldiers and equestrian figures, but also of a group of dramatic sculptures of animals in violent combat with human beings, epitomised by this recently re-discovered example. In 1840 he entered the studio of Jacques-Christophe Werner, lithographer and principal painter at the Musée National d’histoire naturelle in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris. Here he studied anatomy and drew studies of animals from life, later succeeding Antoine-Louis Barye as Professor of Drawing. He was influenced by Barye, famous for his animal sculptures, and also by François Rude, under whom he studied sculpture. At the 1850 Paris Salon Frémiet exhibited a small bronze, Hound licking his wound’ (V&A, 256-1896), which firmly established him as a talented ‘animalier’ sculptor of small-scale works. However, at the same Salon he exhibited a much larger plaster sculpture, Wounded Bear (also titled Bear and Gladiator), the first of his group of works depicting men in aggressive combat with beasts. These ‘combat’ works feature animals modelled with striking verisimilitude, but the focus is on the interaction between man and beast at the culmination of violent and deadly encounter. At the 1859 Salon the jury had rejected Frémiet’s first ‘Gorilla’ sculpture, the Gorilla carrying off a Negress, although this was partially reprieved by the Comte de Nieuwekerke and displayed behind a curtain at the entrance to the Salon. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection (1859) as well as Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861), describing gorillas, would have been known to Frémiet at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Tales of this ferocious, human-like animal in areas of Africa new to Europeans prompted a scramble to acquire gorillas and gorilla parts for collections. The gorilla was central to debates about the place of humans within the order of primates, and Frémiet later recalled, “At a time when a lot of noise was starting to be made about mankind and apes being brothers, it was certainly audacious; and my work proved even more aggravating since, the gorilla being the ugliest of all the primates, the comparison was hardly flattering for humans.” Those debates were still raging when Frémiet made this terracotta in 1876. The sculpture draws upon Frémiet’s direct observation and recording of gorilla specimens at the Natural History Museum in Paris. It is masterly in its execution, the clay partly cast and the surface vigorously tooled to convey the texture of the gorilla’s fur, the gladiator’s hair, net and other accessories. The gladiator is specifically a Retiarius, a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment inspired by that of a fisherman, and he is academically and correctly depicted with only a shoulder guard, net and trident. The composition has the drama of Baroque precedents and in its depiction of Gladiators in combat parallels the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Above all, it encapsulates in visual form the raging debates in the mid-19th century about the supremacy (or not) of humans, international explorations of Africa, and research into the natural world. It is a purposefully arresting work which still shocks today, as it did at the Salon of 1876. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.8-2017 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 5, 2017 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest