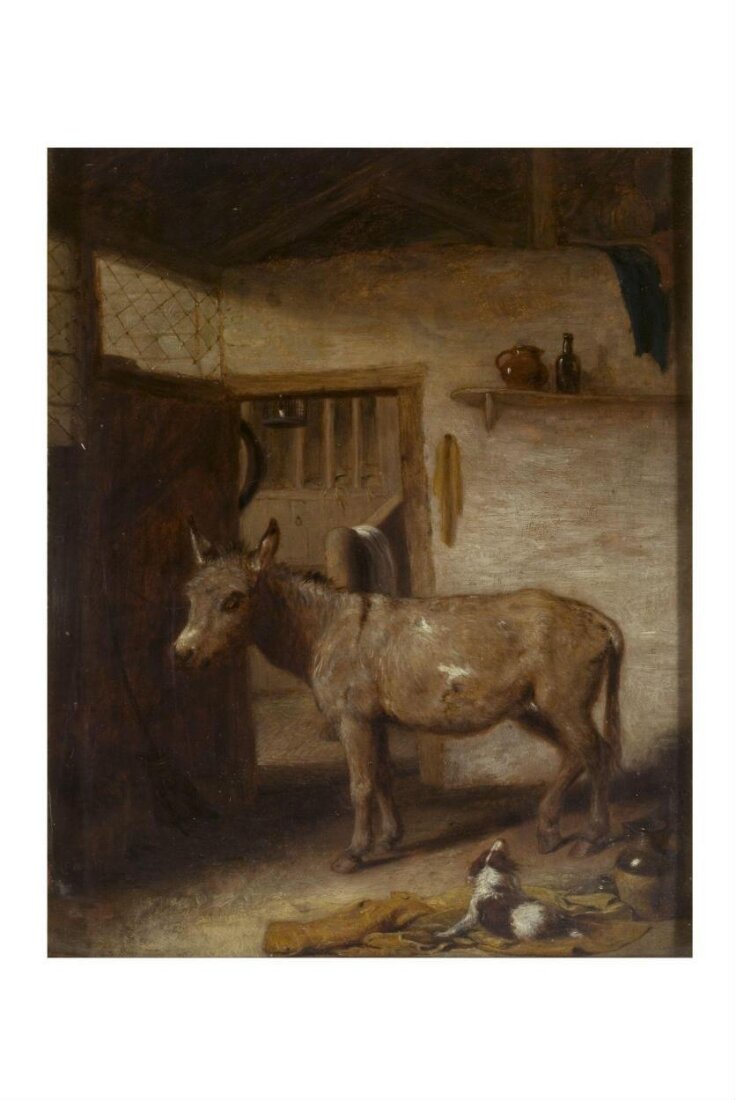

A Donkey and a Spaniel in a Stable

Oil Painting

1818 (painted)

1818 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Rustic scenes such as this one, showing a Donkey and Spaniel contemplating each other, became popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Cooper was known for painting horses. His understanding of animals' character and anatomy can be seen in this depiction of the donkey. The inclusion of everyday objects like jugs and bottles the rustic convey the rustic theme of the work. At the same time these objects demonstrate Cooper's ability to paint both animate and inanimate things.

Cooper was known for painting horses. His understanding of animals' character and anatomy can be seen in this depiction of the donkey. The inclusion of everyday objects like jugs and bottles the rustic convey the rustic theme of the work. At the same time these objects demonstrate Cooper's ability to paint both animate and inanimate things.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | A Donkey and a Spaniel in a Stable |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on panel |

| Brief description | Oil painting entitled 'A Donkey and a Spaniel in a Stable' by Abraham Cooper. Great Britain, 1818. |

| Physical description | Oil on panel depictings a donkey and a spaniel sheltering in a stable |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | 'AC [monogram] 1818' (Signed and dated by the artist) |

| Credit line | Given by John Sheepshanks, 1857 |

| Object history | Given by John Sheepshanks, 1857 as part of his collection of 233 oils and 298 watercolours, etchings and drawings John Sheepshanks (1787-1863), art collector, was the son of the wealthy cloth manufacturer and merchant Joseph Sheepshanks. John succeeded his father in the family firm of York and Sheepshanks in Leeds. After his retirement from business in 1827, John Sheepshanks moved to London. He made several trips to the Continent but lived relatively modestly. Apart from art, Sheepshanks was interested in gardening and was a member of both the Royal Horticultural Society and the Athenaeum Club. Sheepshanks liked to pursue his interest in art by entertaining painters and engravers at informal Wednesday "at homes". Sheepshanks began his interest in art through collecting books of Dutch and Flemish prints. Before he moved to London he made purchases at the Northern Society in Leeds. In London he actively patronized artists including Landseer, Mulready, Leslie, Callcott and Cooke. His taste was for contemporary early Victorian cabinet pictures of anecdotal, sentimental, and instructive subjects, as well as scenes from literature. His collection was unique for its time being the only large scale one of contemporary British paintings. He gave his collection to the South Kensington museum in 1857 (see departmental file on Sheepshanks). The deed of gift stipulated that "a well-lighted and otherwise suitable" gallery should be built to house his collection near the buildings of the Science and Art department on the South Kensington Site. This followed Sheepshanks' wish to create a 'gallery of British art'. The Sheepshanks Gallery was opened in 1857. Historical significance: Abraham Cooper (1787-1868), painter of battle and animal subjects, was born in London, where he worked throughout his life. While still a boy at school, Cooper showed an aptitude for drawing animals and particularly horses. At the age of thirteen he went to work for his uncle, William Davis, who was the manager of Astley's circus. The circus was famous for its equestrian shows. This provided Cooper with the opportunity to study horses at first hand. Around 1809, determined to become an artist, he bought a book on oil painting and began to teach himself the technique. Around this time he became acquainted with the celebrated horse painter Benjamin Marshall (1768-1835) through William Davis. Marshall gave him space in his studio and introduced him to prospective patrons. Cooper exhibited at both the Royal Academy and British Institution for the first time in 1812. He was elected Royal Academician in 1820. This was only seven or eight years since he had begun painting in oils. He initially painted animal scenes but from 1817 he also began to paint battle scenes. This painting shows a donkey accompanied by a dog in a stable. Light falls through the open doors in the back left corner of the scene, illuminating the animals. Cooper captures the individual characters of each animal by contrasting the way that the donkey cautiously looks down at the spaniel, who busily scratches its chin with its right hind leg. The portrayal of each animal and their character anticipates the work of the great Victorian animal painter Edwin Landseer (1802-1873).Broad brushstrokes have been used to convey the shaggy texture of the donkey's coat, which contrasts with the silky fur of the spaniel. The tones of the donkey’s fur are echoed in those of the surroundings, which are painted in shades of greys and browns. In the foreground of the painting the glaze of an earthenware jug contrasts with the matt texture of the floor. Placing such objects in the painting demonstrates the artist's skill at representation. The inclusion of these objects also reflects the art of earlier Dutch seventeenth-century masters such as Jan Steen (1626-1679). At the same time by placing these objects in the foreground Cooper is able to demonstrate his skill at representation of objects of different material. This painting, along with FA.51 (A Grey Horse at a Stable Door, is one of two by Abraham Cooper given to the museum by John Sheepshanks (1787-1863) in 1857. There is no surviving record of the provenance of these two paintings before they entered the V&A collections. Sheepshanks was a great patron of contemporary British Art and it is likely that he would have commissioned or bought these two works directly from the artist. It has been suggested that this and another Cooper painting acquired by the museum at the same time (FA.50) were conceived of as a pair (see note on object file). The donkey is shown facing to the left in FA. 50 whilst the horse in FA 51 faces to the right. This and the matching dimensions of these two works confirm that these two works were made to be hung together as pendants. |

| Historical context | The tradition of representing animals in art can be traced back to prehistoric times. However the genre of animal subjects grew in Western art following the Renaissance. This was partly in response to newly discovered species that European explorers brought back from the New World. The growing interest in this subject was also in response to the reappraisal of the Christian interpretation of the relation between humanity and the rest of creation. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries an increasing interest in realism began to appear in the treatment of animal subjects in the work of artists such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Albrecht Durer (1471-1528). Whilst animals often appear as part of paintings during this period, they were never the focus of an entire composition. Developments in this occurred in the sixteenth-century graphic arts. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is Durer's woodcut of a Rhinoceros (1515). The interest in zoological imagery was further developed by the Swiss naturalist Konrad Gessner's (1515-1565) fundamental publication of the Historia animalium (5 vols, Zurich, 1551-1587). In response to the discovery of the New World Theodor de Bry (1528-1598) published woodcuts of marine organisms and sea monsters in his volume America (c.1590). This interest in animal imagery that had been explored in the graphic arts of the sixteenth century began to evolve into a genre of painting during the following century. Rubens'(1577-1640) studio in Antwerp was particularly important for the development of animal subjects. In a number of his works, such as Daniel in the Lion's Den (c.1615; National Gallery of Art, Washington), animals become the focal point of the composition. A similar interest in animals can also be seen in the work of Snyders (1579-1657) and Paul de Vos (1591-92 or 1595-1678), both of whom were pupils of Rubens. As the taste for natural realism became increasingly popular, many seventeenth-century artists including Frans Snyders and Jacob Bogdani (1660-1724) began to introduce animal subjects in to still-life paintings. During the eighteenth century the most significant developments in animal painting took place in France and Great Britain. In the early eighteenth century animals were still included in landscapes, historical scenes, military subjects, sporting scenes, portraits, and still-lifes. However as a separate subject they were considered to have less artistic significance as they were imitative of nature. With its social and sentimental overtones the animal portrait would eventually emerge as a popular sub-genre in Europe and particularly in Britain. In the eighteenth-century Britain, animal painting enjoyed unrivalled popularity. An increasing number of artists including James Seymour (1702-1752), Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), and James Ward (1769-1859) specialised in animal subjects during the century. The most significant animal painter of the period was George Stubbs (1724-1806). His works encompassed a wide variety of genres including sporting scenes and portraits as well as animals in violent combat. Towards the end of the century a number of artists were focusing on portraits of breeds of cattle, poultry, pigs and sheep. These works reflected both agricultural improvements and nationalistic concerns during a period of international turmoil. The beginning of the nineteenth century witnessed an increased interest in animal subjects. This was the result of the gradual breakdown of the traditional hierarchy of genres. Many of the themes remained the same as those developed during the eighteenth century. However the nineteenth century saw artists beginning to particularise animals and use a more intense palette. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Rustic scenes such as this one, showing a Donkey and Spaniel contemplating each other, became popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Cooper was known for painting horses. His understanding of animals' character and anatomy can be seen in this depiction of the donkey. The inclusion of everyday objects like jugs and bottles the rustic convey the rustic theme of the work. At the same time these objects demonstrate Cooper's ability to paint both animate and inanimate things. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | FA.50[O] |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 17, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest