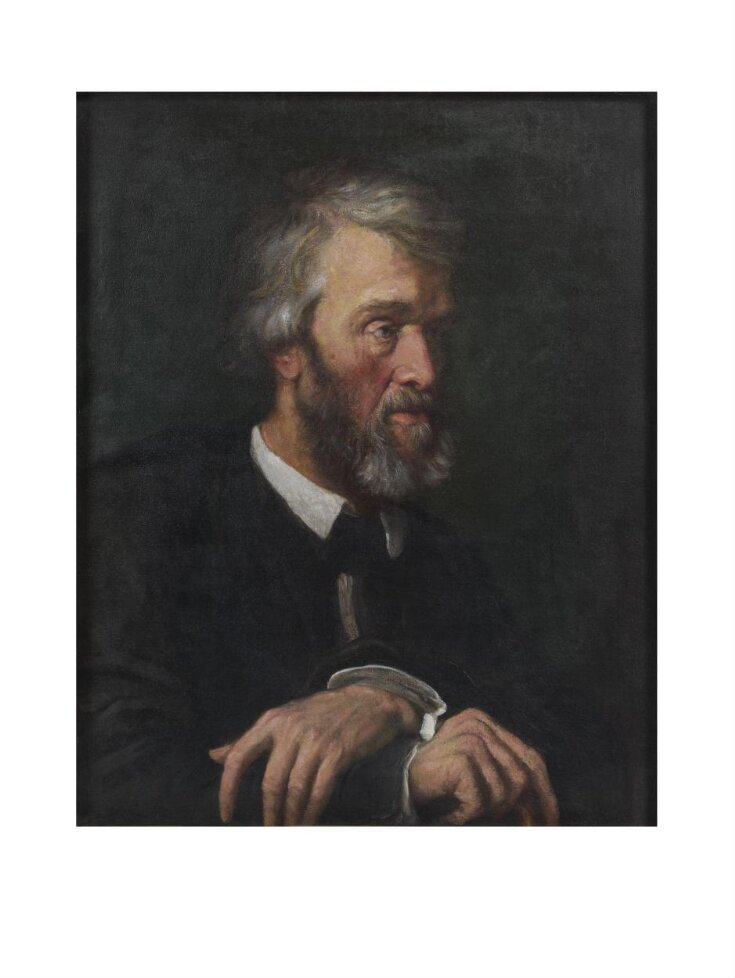

Thomas Carlyle

Oil Painting

1868 (painted)

1868 (painted)

| Artist/Maker |

Oil painting, 'Thomas Carlyle', George Frederick Watts, 1868

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Thomas Carlyle |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on canvas |

| Brief description | Oil painting, 'Thomas Carlyle', George Frederick Watts, 1868 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by John Forster |

| Object history | Bequeathed by John Forster, 1876 George Frederick Watts was born on 23 September, 1817. He received no regular schooling on account of poor health, but later studied under the sculptor William Behnes and entered the R.A schools in 1835. In 1837 he achieved recognition for The Wounded Heron (Compton, Watts Gallery), exhibited at the R.A. Watts won a prize of £300 for his painting Caractacus in the 1843 Westminster Hall competition. He went to Florence until 1847, where he worked under the patronage of Lady Holland. On his return to England, Watts won a further prize of £500 in the Westminster Hall competition for his Alfred inciting the Saxons to prevent the landing of the Danes. Inspired by Michelangelo and with his reputation now firmly established, Watts was determined to devote himself to grand, universal themes such as Faith; Hope; Charity; Love and Life; and Love and Death. However he rose to front rank as a portrait painter and painted many of his eminent contemporaries including Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill, William Gladstone and John Everett Millais. He was elected to the A.R.A and R.A in 1867. In 1864 he married 16-year-old Ellen Terry and painted a charming allegorical portrait of her, Choosing, but the couple separated the following year. A major late sculpture, Physical Energy (1904, London, Kensington Gardens) is surprisingly modernistic. Watts presented many of his works to art galleries and institutions. He died on 1 July, 1904. Watts’ portrait of Thomas Carlyle, commissioned by John Forster, was painted between June 1867 and July 1868. Although there is evidence that a mutual respect existed between Carlyle and Watts, the painting of the portrait did not go smoothly. Carlyle, the ‘Philosopher’ or ‘Sage’ of Chelsea, was widely respected as the foremost social critic of the age and it is known that Carlyle thought Watts to be a ‘man of note.’(1) Despite this, there appears to have been a character clash that was not conducive to the creation of this portrait. On 20th May, just prior to the commencement of the work Carlyle wrote to Forster ‘I am to give Watts his “first sittings” (sorrow on it),’(2) suggesting his less than enthusiastic view of the task at hand, and during the sittings themselves it has been recorded that Carlyle did not attempt to hide his boredom and frequently asked when the sitting would be over.(3) Watts felt that conversation was necessary to create a successful portrait where the real man is brought forth and, in such a prickly environment where he felt it difficult to establish sympathy with the sitter, he found it hard to progress. Furthermore, Watts had often felt that ‘Nature did not intend me for a portrait-painter’ (4) and his wife Mary Seton Watts has recorded that this commission, which was deemed by Watts to be a failure, more than ever confirmed this opinion.(5) Watts’ condemnation of this work seems justified as on seeing it Carlyle declared that Watts had made him ‘a delirious-looking mountebank, full of violence, awkwardness, atrocity, and stupidity, without recognisable likeness to anything I have ever known in any feature of me!’ However, John Forster was content with the portrait and some critics were eminently favourable. For example G. K. Chesterton, in his appraisal of Watts’ work, has written that ‘Watts’ Carlyle is immeasurably more subtle and true than the Carlyle of Millias... the uglier Carlyle of Watts has more of the truth about him.’(6) There are two further versions of this composition. It is thought that Watts initially worked on all three simultaneously. One, which was finished later, is in the National Portrait Gallery and is similar in most aspects except for its omission of the hands. The whereabouts of the other, which was saved from destruction by Mary Seton Watts and is incomplete, is unknown. References: 1) Gould, Veronica Franklin, G. F. Watts: The Last Great Victorian, (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2004), p.91 2) Ibid. 3) Barrington, Mrs Russell, Reminiscences of G. F. Watts, (London: George Allen, 1905), p.33 4) Watts, M. S., George Frederick Watts (vol I), (London: Macmillan & Co, 1912), p.208 5) Ibid. p.248 6) Chesterton, G. K., G. F. Watts (London: Duckworth & Co., 1904), p.69 Bibliography Barrington, Mrs Russell, Reminiscences of G. F. Watts, (London: George Allen, 1905) Bryant, Barbara, G. F. Watts Portraits: Fame and Beauty in Victorian Society, (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2004) Chesterton, G. K., G. F. Watts (London: Duckworth & Co., 1904) Gould, Veronica Franklin, G. F. Watts: The Last Great Victorian, (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2004) Sketchley, R. E. D., George Frederic Watts, (London: Methuen & Co., 1904) Watts, M. S., George Frederick Watts (vols I & II), (London: Macmillan & Co, 1912) |

| Subject depicted | |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | F.39 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 20, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest