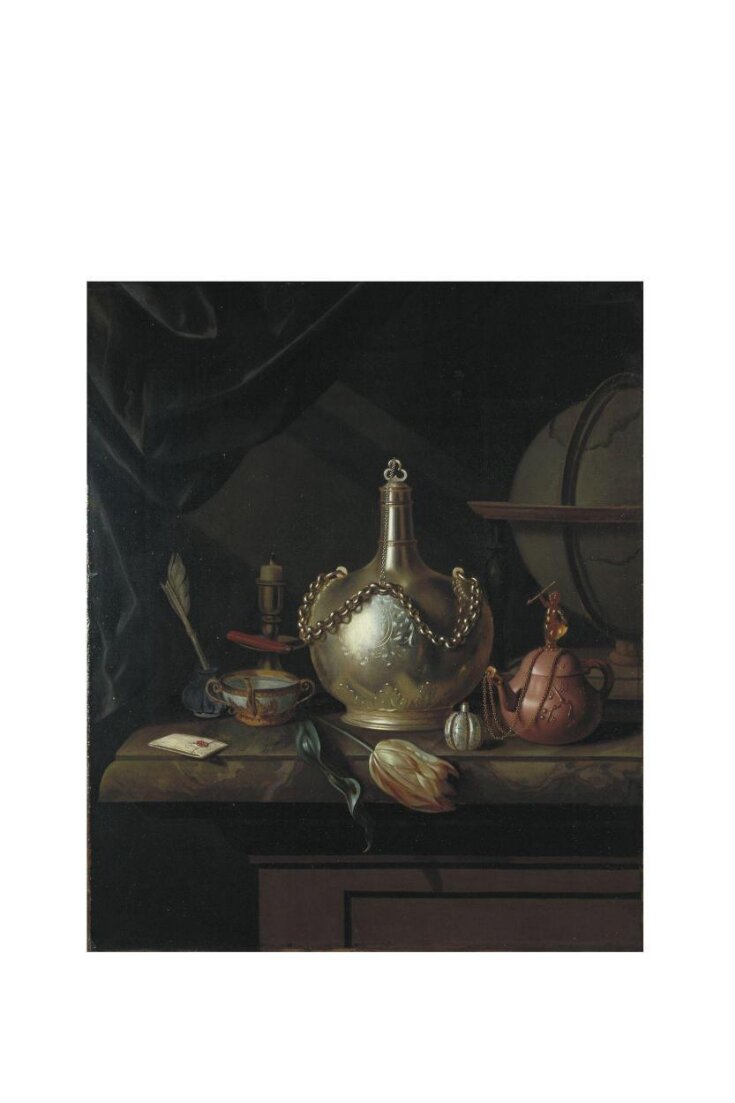

Still Life with Silver Wine Decanter, Tulip, Yixing Teapot and Globe

Oil Painting

ca. 1690 (painted)

ca. 1690 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

A marble table-top with a silver chained vessel at centre flanked by an inkwell and quill, brass candlestick with snuffed candle and a Chinese porcelain feeding cup at left and an enamelled copper scent-flask and chained earthenware teapot at right. A tulip hangs over the edge of the table. Pieter (Gerritsz.) van Roestraten, (1629/30-1700) was a Dutch painter, apprenticed to Frans Hals in Haarlem until 1651 and married to his daughter from 1654. Sometime between 1663 and 1665 he went to London where he specialised in rich and decorative flower paintings and still-lifes, strongly influenced by the luxurious pronk stilleven style of the Amsterdam painter Willem Kalf. Roestraten artist was renowned for his skillful depiction of silver (candlesticks, porringers, wine coolers and tea caddies), lacquered objects, porcelain, and especially the English red stoneware teapots and cups so much in favour at the time. Good examples are the Still life with a Silver Candlestick (Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen) and Still-life with a Theorbo (London, Buckingham Pal., Royal Col.). In London, van Roestraten painted primarily costly objects for English aristocrats, many of his paintings virtual 'portraits' of objects they owned. P.5-1939 presents tea as a costly luxury, represented by a redware trekpotje nearly identical to that depicted in Roestraeten's Still Life with Silver candleholder (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, inv. no. 131). In the corresponding location on the right of the silver wine decanter (ca. 1690, probably Dutch) a paper packet of tea with its wax seal is placed among other previous objects, including a tulip, representing another fashionable trade that was more notoriously Dutch. The impact of the arrival of tea in Holland however was much was the same in England : within both cultures, afternoon tea became permanently instituted as a daily ritual. The trade in tea is a particularly clear instance of how a close interaction of distant cultures can generate changes in the very patterns of everyday life. Consequently, this still life functions as a kind of showpiece of exotic and costly goods painted for the English aristocracy, yet still in a distinctly Dutch tenor.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Title | Still Life with Silver Wine Decanter, Tulip, Yixing Teapot and Globe (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on canvas |

| Brief description | Oil painting, 'Still Life with Silver Wine Decanter, Tulip, Yixing Teapot and Globe', Pieter van Roestraten, ca. 1690 |

| Physical description | A marble table-top with a silver chained vessel at centre flanked by an inkwell and quill, brass candlestick with snuffed candle and a Chinese porcelain feeding cup at left and an enamelled copper scent-flask and chained earthenware teapot at right. A tulip hangs over the edge of the table |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | 'P. Roestraten' (Signed by the artist at the base of the table) |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by Lionel A. Crichton |

| Object history | Bequeathed by Lionel A. Crichton, 1939 Historical significance: Pieter (Gerritsz.) van Roestraten, (1629/30-1700) was a Dutch painter, apprenticed to Frans Hals in Haarlem until 1651 and married to his daughter from 1654. Sometime between 1663 and 1665 he went to London where he specialised in rich and decorative flower paintings and still-lifes, strongly influenced by the luxurious pronk stilleven style of the Amsterdam painter Willem Kalf. Roestraten was renowned for his skillful depiction of silver (candlesticks, porringers, wine coolers and tea caddies), lacquered objects, porcelain, and especially the English red stoneware teapots and cups so much in favour at the time. Good examples are the Still life with a Silver Candlestick (Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen) and Still-life with a Theorbo (London, Buckingham Pal., Royal Col.). In London, Roestraten painted primarily costly objects for English aristocrats and many of his paintings are virtual 'portraits' of objects they owned. P.5-1939 presents tea as a costly luxury, represented by a redware trekpotje, nearly identical to that depicted in Roestraeten's Still Life with Silver candleholder (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, inv. no. 131). In the corresponding location on the right of the silver wine decanter (ca. 1690, probably Dutch) a paper packet of tea with its wax seal is placed among other precious objects, including a tulip, representing another fashionable trade that was more recognisably Dutch. Another juxtaposition of Dutch with foreign objects is the Chinese porcelain feeding cup in a Dutch silver-gilt mount of ca. 1650. The brass candlestick is also Dutch, ca. 1670, and holds a smoking candle, a traditional vanitas symbol alluding to human mortality and the passage of time. With the Dutch tulip front and centre, and the globe in the background, issues of international economics may well be invoked here, a notion which raises further questions considering that the work was painted by a Dutch artist, working in London for an English clientele. The impact of the arrival of tea in Holland however was much the same in England: within both cultures, afternoon tea became permanently instituted as a daily ritual. The trade in tea is a particularly clear instance of how a close interaction of distant cultures can generate changes in the very patterns of everyday life. Consequently, this still life functions as a kind of showpiece of exotic and costly goods painted for the English aristocracy, yet still in a distinctly Dutch tenor. |

| Historical context | The term 'still life' conventionally refers to works depicting an arrangement of diverse inanimate objects including fruits, flowers, shellfish, vessels and artefacts. The term derives from the Dutch 'stilleven', which became current from about 1650 as a collective name for this type of subject matter. Still-life reached the height of its popularity in Western Europe, especially in the Netherlands, during the 17th century although still-life subjects already existed in pre-Classical, times. As a genre, this style originates in the early 15th century in Flanders with Hugo van der Goes (ca.1440-1482), Hans Memling (ca.1435-1494) and Gerard David (ca.1460-1523) who included refined still-life details charged with symbolic meaning in their compositions in the same manner as illuminators from Ghent or Bruges did in their works for decorative purpose. In the Low Countries, the first types of still life to emerge were flower paintings and banquet tables by artists like Floris van Schooten (c.1585-after 1655). Soon, different traditions of still life with food items developed in Flanders and in the Netherlands where they became especially popular commodities in the new bourgeois art market. Dutch painters played a major role the development of this genre, inventing distinctive variations on the theme over the course of the century while Flemish artist Frans Snyders' established a taste for banquet pieces. These works were developed further in Antwerp by the Dutchman Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684) who created opulent baroque confections of fruit, flowers, and precious vessels that became a standardized decorative type throughout Europe. Scholarly opinion had long been divided over how all of these images should be understood. The exotic fruits and valuable objects often depicted testify to the prosperous increase in wealth in cities such as Amsterdam and Haarlem but may also function as memento mori, or vanitas, that is, reminders of human mortality and invitations to meditate upon the passage of time. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | A marble table-top with a silver chained vessel at centre flanked by an inkwell and quill, brass candlestick with snuffed candle and a Chinese porcelain feeding cup at left and an enamelled copper scent-flask and chained earthenware teapot at right. A tulip hangs over the edge of the table. Pieter (Gerritsz.) van Roestraten, (1629/30-1700) was a Dutch painter, apprenticed to Frans Hals in Haarlem until 1651 and married to his daughter from 1654. Sometime between 1663 and 1665 he went to London where he specialised in rich and decorative flower paintings and still-lifes, strongly influenced by the luxurious pronk stilleven style of the Amsterdam painter Willem Kalf. Roestraten artist was renowned for his skillful depiction of silver (candlesticks, porringers, wine coolers and tea caddies), lacquered objects, porcelain, and especially the English red stoneware teapots and cups so much in favour at the time. Good examples are the Still life with a Silver Candlestick (Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen) and Still-life with a Theorbo (London, Buckingham Pal., Royal Col.). In London, van Roestraten painted primarily costly objects for English aristocrats, many of his paintings virtual 'portraits' of objects they owned. P.5-1939 presents tea as a costly luxury, represented by a redware trekpotje nearly identical to that depicted in Roestraeten's Still Life with Silver candleholder (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, inv. no. 131). In the corresponding location on the right of the silver wine decanter (ca. 1690, probably Dutch) a paper packet of tea with its wax seal is placed among other previous objects, including a tulip, representing another fashionable trade that was more notoriously Dutch. The impact of the arrival of tea in Holland however was much was the same in England : within both cultures, afternoon tea became permanently instituted as a daily ritual. The trade in tea is a particularly clear instance of how a close interaction of distant cultures can generate changes in the very patterns of everyday life. Consequently, this still life functions as a kind of showpiece of exotic and costly goods painted for the English aristocracy, yet still in a distinctly Dutch tenor. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | P.5-1939 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 6, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest