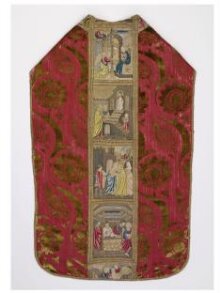

Chasuble

1425-1450 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This is a chasuble, the vestment (priestly garment) worn by a Catholic priest when celebrating the mass (the main service of worship). Prior to the 1960s, the priest stood facing the altar with his back to the congregation, so the back of the chasuble was visible most of the time. The front is more worn than the back because it has rubbed against the altar. The embroidery on the orphrey bands tells the story of the Life of the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, from the moment the angel announced her forthcoming birth to her mother St Anne, until her journey to heaven after her death.

The silk velvet of the chasuble was probably made in Italy, which boasted the most sophisticated centres of silk manufacturing in Europe in the 15th century. The style of the embroidery on the orphreys is very similar to Florentine paintings of the early to mid-15th century. The shape dates to the 17th century or later. Precious silk and fine embroidery, especially containing metallic threads, were used economically and were often recycled.

The silk velvet of the chasuble was probably made in Italy, which boasted the most sophisticated centres of silk manufacturing in Europe in the 15th century. The style of the embroidery on the orphreys is very similar to Florentine paintings of the early to mid-15th century. The shape dates to the 17th century or later. Precious silk and fine embroidery, especially containing metallic threads, were used economically and were often recycled.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Voided velvet, with embroidered orphreys (silk, silver and silver gilt on linen) |

| Brief description | Chasuble, green and red voided velvet, embroidered orphreys; probably Italy; 15th century |

| Physical description | Violin- or shield-shaped chasuble of voided silk velvet with green pile and red satin ground, embroidered orphreys have been appliqued to ground. The embroidery has been built up from a base of linen, stitched in coloured silk (in three shades of green, of blue and of red), silver, and silver-gilt thread, in couching, and long and short stitch. The ground of the embroidery is executed in different textures and fillings of metallic thread, and some of it is raised work. The pattern on the velvet consists of an interrupted wavy diagonal stem, bearing on one side conventionalised pine-cones, and on the other pomegranates in a circle of leaves. This pattern is seen best on the back of the chasuble as the front has been pieced together. The back is also much less worn than the front, revealing the construction of the embroidery. It is lined in blue linen. Iconography The orphreys depict scenes from the Life of the Virgin, mainly on backgrounds of gold and silver and were originally intended for a cope rather than a chasuble. They have been mutilated when recycled, the lowest compartment of the design cut to suit the length of the chasuble, and two of the remaining compartments used to trim the neckline. They have been unsympathetically used, so that the same scene is at the same level, but cannot be read left to right. Each scene comprises a group of people in an architectural setting, definitely classical in line rather than Gothic.The folds on the clothing of the figures are very carefully delineated. Round the neck: (1) the death of the Virgin, lying on a bed surrounded by the Apostles, and (2) the Assumption of the Virgin, borne up by angels with St Thomas by the tomb below. On the back: (1) the Anunciation; the Virgin seated, the Angel kneeling, God the Father appearing in the clouds and the Dove descending; (2) the presentation of the Virgin in the Temple; she ascends the stair to the High Priest, her parents, St Anna and St Joachim, wait below; (3) the meeting of St Anna and St Joachim; they embrace before the Golden Gate of Jerusalem, an angel touches their heads and a manservant and maidservant attend them; (4) the rejection of St Joachim's offering: he carries away a lamb from the altar behind which three priests are sitting or standing; (5) the angel appearing to St Joachim among the shepherds, the lower part is missing. On the front orphrey: (1) the Announcement of the approaching death of the Virgin, she is seated, the angel bearing the palm kneels to her, behind her stand a group of the Apostles; (2) the betrothal of the Virgin to St Joseph; the priest joins their hands in the presence of St Anna and three suitors; the two figures on the extreme outer edges are very fashionable dressed for the mid 15th century (3) the birth of the Virgin; St Anna in bed, a woman beside her and a servant bringing a bowl, the lower part cut away. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Production type | Unique |

| Gallery label | CHASUBLE.

ITALIAN; 1425-50

Reading upwards, the Birth of the Virgin, the Marriage of the Virgin, the Annunciation of the Virgin's death; St Catherine, The Virgin and Child, and St John the Evangelist; about the neck, mutilated scenes of the Death of the Virgin and her Assumption. The ophrey, which was originally intended for use on a cope, is embroidered with silver and silver-gilt thread in laid and couched work, and with coloured silks in split silver and silver-gilt thread in laid and couched work, and with coloured silks in split stitch, on linen.

The velvet (zetuni vellutati) of which the vestment is made is also Italian.

329-1908.(1960s?) |

| Object history | Purchased from Lady Battersea for £84 in June 1908. When acquired, the chasuble was in two parts, both described as 'damaged and repaired'. It was joined up in the 'art workroom'. The chasuble had been offered to the Museum for sale on the occasion that Lady Battersea gave the Museum an altar frontal (2490-1908). Expert views on the object came from E.R.D. Maclagan on 6/06/1908, from P.Trendell on 11/06/1908 and A.F. Kendrick on 11/06/1908. All agreed that the chasuble was Italian, the embroidery probably Florentine of the first quarter of the fifteenth century, the velvet somewhat later in the century. Maclagan compared the embroidery with the earlier and finer treatment of the Life of the Virgin on 831-1903 and the panel with the death of St Viridiana (4216-1857) of about the same date. He noted that embroidery of this period was not well-represented in the Museum. Trendell considered the floral pattern on the velvet ground particularly effective, and the embroidery of the orphreys very rich. He also noted that at that time the Museum had only one complete chasuble (7788-1862) with fifteenth century orphreys of similar character, and that the price asked was not excessive. On 20/06/1908 A. B. Skinner noted that the price was good, comparing it as a purchase of eleven panels of a complete chasuble, with the £130 paid for the nine panels representing the life of the Virgin in 1903, the £67 for a chasuble of fifteenth century Italian brocaded damask with English orphreys in 1901, £91 for a chasuble of Italian damask with sixteenth century French orphreys in 1903, and the £103 for a chasuble of Florentine velvet with English orphreys in 1907. Paid on 17/07/1908. (MA/1/B723). Historical significance: This vestment is significant as an example of the investment that went into the creation of suitable attire for the church: the materials are inherently precious (real silver and silver-gilt threads; imported silk), the labour required in the creation of such superlative embroidery and the weaving of fine velvet extremely skilled. The recycling of the silk and the embroidery at a later date into this particular vestment indicates the value attached to such materials. |

| Historical context | Garment and materials The chasuble is an example of the richly decorated vestments commissioned for use in the Church. This particular example is typical of the International Gothic style favoured in the fifteenth centuries, the silk velvet characterised by scrolling motifs consistent with a dating of the late fifteenth century. Such a silk was suitable for both secular and ecclesiastical use, and might have been made in an Italian or Spanish centre (the most developed in Europe at this time). At that period chasubles were conical in shape, rather than fiddle- or violin-shaped, so this garment must have been altered at a later date (after the beginning of the seventeenth century). The silk may even have begun its life as a different form of dress or furnishing altogether, no major distinction between secular and ecclesiastical designs being made at that time. The orphreys may well date to earlier in the century, their composition and treatment being similar to Italian paintings of the 1420-50 period. The dimensions of the compartments of the orphreys may be useful eventually in identifying the geographical location of making (when guild regulations become easily accessible for different cities). Currently, identification can only be speculative, based on the aesthetics of the images. It is possible that these orphrey bands were originally intended/used for a cope. The embroidery was probably executed either in a professional workshop (urban or church) or by nuns. Certain similarities with the needlework image of St Verdiana (Viridiana) (4216-1857) in terms of composition and architectural setting are very evident; it is thought to be Florentine. Iconography of orphreys The Life of the Virgin is told in the embroidered panels on the orphreys in eight vignettes, including the Annunciation and Assumption. Rogers and Tinagli note that from as early as the 2nd century, Mary's virtues of humility, obedience, modesty and silence were extolled in contrast to Eve's negative characteristics, and that in the early fifteenth century such ideas were communicated to a wider audience visually via Fra Angelico's Annunciation scenes, and verbally by preachers such as the Franciscan Bernardino da Siena (e.g. in a 1427 sermon). Devotional activities focussed on different aspects of her life and were encouraged in Italy by both the church and the state, and many groups - not just women - felt drawn to her cult. Rosika Parker suggests that 'heroic women who transcended in virtue all women and all humans' became a popular theme in Renaissance writing, and that they were increasingly portrayed as meek and domesticated figures. At this time, celebrations of the Assumption of the Virgin were increasingly embroidered on ecclesiastical vestments , complementing her image as Mary the mother. In this representation, the architectural sets and the scenes with her parents undoubtedly stress her humanity as well as the importance of her role as the mother of Jesus Christ. (Mary Rogers and Paola Tinagli, Women in Italy, 1350-1650. Ideals and Realities. Manchester University Press, 2005, pp.17-8, 42-55; Rosika Parker, The Subversive Stitch. The Women's Press, 1984, pp. 65-6). |

| Production | Based on pattern on velvet and imagery on orphreys Attribution note: Most ecclesiastical vestments were made specially for a particular church or clergyman although their materials and adornment were often very similar to others. Reason For Production: Commission |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | This is a chasuble, the vestment (priestly garment) worn by a Catholic priest when celebrating the mass (the main service of worship). Prior to the 1960s, the priest stood facing the altar with his back to the congregation, so the back of the chasuble was visible most of the time. The front is more worn than the back because it has rubbed against the altar. The embroidery on the orphrey bands tells the story of the Life of the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, from the moment the angel announced her forthcoming birth to her mother St Anne, until her journey to heaven after her death. The silk velvet of the chasuble was probably made in Italy, which boasted the most sophisticated centres of silk manufacturing in Europe in the 15th century. The style of the embroidery on the orphreys is very similar to Florentine paintings of the early to mid-15th century. The shape dates to the 17th century or later. Precious silk and fine embroidery, especially containing metallic threads, were used economically and were often recycled. |

| Associated object | 4216-1857 (Depiction) |

| Bibliographic reference | Lisa Monnas, Merchants, Princes and Painters. Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings 1300-1500. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008, p. 99, fig. 100; p. 107, fig. 109; and in the text, pp. 98, 106 and 108. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 329-1908 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 22, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest