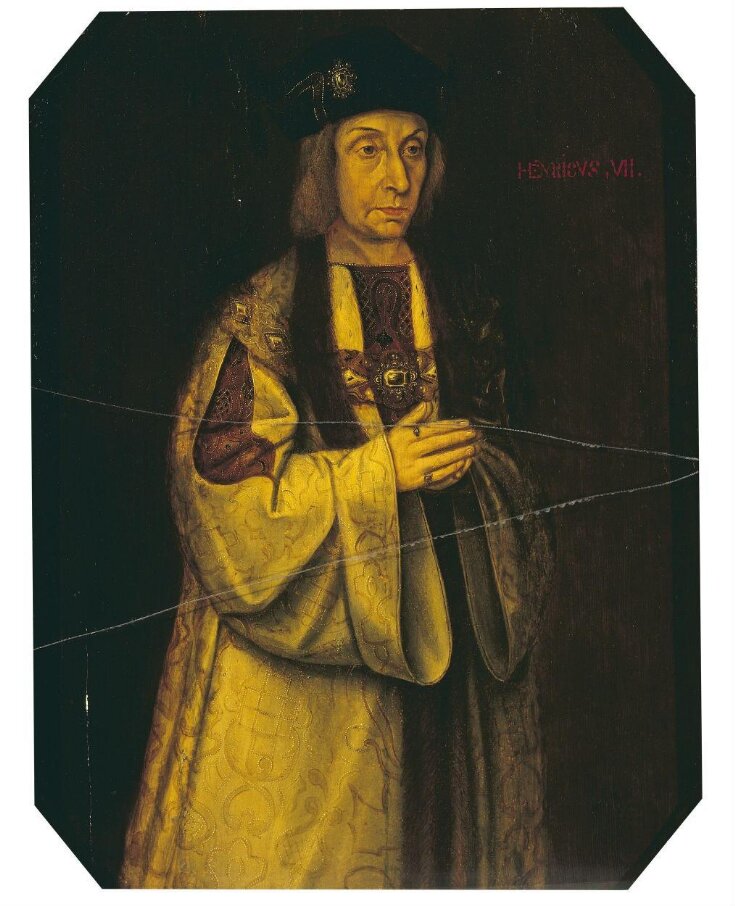

Henry VII (1457-1509)

Oil Painting

16th century (made)

16th century (made)

| Artist/Maker |

Oil painting, 'Henry VII (1457-1509)', British School, style of 16th century

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Henry VII (1457-1509) (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on oak panel |

| Brief description | Oil painting, 'Henry VII (1457-1509)', British School, style of 16th century |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by John Forster |

| Object history | Given to the Museum by John Forster (1812-1876, writer and literary adviser) in 1876. John Forster (1812-1876) was born in Newcastle, the son of a cattle dealer. Educated at Newcastle Grammar School and University College London, he was a student in the Inner Temple 1828 and qualified as a barrister 1843. Began his career as a journalist as dramatic critic of the True Sun 1832; he later edited the Foreign Quarterly Review (1842-3), the Daily News (1846) and most famously the Examiner (1847-55). He was the author of numerous works, notably the Life and Adventures of Oliver Goldsmith (1848) and the Life of Charles Dickens (1872-4). He bequeathed his extensive collection of books, pamphlets, manuscripts, prints, drawings, watercolours and oil paintings to the V&A. See also South Kensington Museum Art Handbooks. The Dyce and Forster Collections. With Engravings and Facsimiles. Published for the Committee of Council on Education by Chapman and Hall, Limited, 193, Piccadilly, London. 1880. Chapter V. Biographical Sketch of Mr. Forster. pp.53-73, including 'Portrait of Mr. Forster' illustrated opposite p.53. Historical significance: Henry the VII (1447-1509), was the son of Edmund Tudor (1431-1456), Earl of Richmond and head of the house of Lancaster, and Margaret Beaufort (1443-1509). Henry VII was brought up in Wales by his uncle Jasper Tudor. After defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, Henry successfully claimed the English throne. His claim to the throne was strengthened by the fact that his mother was a member of the House of Beaufort. He was crowned King of England and Lord of Ireland in 1485. His reign began the Tudor Dynasty, which ran from 1485 to 1603. In 1486 married Elizabeth, Princess of York (1465-1503), daughter of Edward IV (1442-1483). This marriage unified the previously opposed houses of Lancaster and York. It also strengthened Henry VII's role as king, whilst making all his children rightful heirs to the throne. This three quarter length portrait is longer than most of Henry VII, which are generally bust length. A portrait of Elizabeth of York (V&A inventory number F.46) was bequeathed by Forster along with F.45. The similar dimensions and composition suggest that these were created as pendants, to be displayed together. The fact that the sitters each turn to face each other further strengthens this possibility. The sitter stands against a dark background. This compositional feature was introduced by Netherlandish artists. The King favoured foreign artists, especially those from the Netherlands and Flanders. The inscription "HENRICVS, VII" at the top right of the panel identifies the sitter. He wears long robes of cream and gold figured silk. The sleeves are slashed at the elbows to reveal a tunica of dark red brocade underneath. As with most portraits of Henry VII, he is shown wearing a cap ornamented with a jewelled brooch. Around his neck is a chain of office. The Italian historian Polydor Vergil (1470-1555), describing the King's appearance, wrote: "His body was slender but well built and strong; his height above average. His appearance was remarkably attractive and his face was cheerful, especially when speaking; his eyes were small and blue, his teeth few, poor and blackish; his hair was thin and white; his complexion sallow" (Polydor Vergil, Anglica Historia 1485-1537, published 1557, [RHS Camden Series Vol. 74, ed. Denys Hay). The majority of portaits of Henry VII are bust length and few in this longer format survive. One other example is the full length figure of the King in Holbein's Privy Chamber fresco at Whitehall of 1537 (see J. Rowlands, Holbein, Oxford, 1985, p. 225, no. L.14.) A copy by Remigiius van Leemput of this lost work is in the Royal Collection and the cartoon for the original fresco is at the National Portrait Gallery, London). In the cartoon the King is shown in similar robes. His features suggest that, as with F.45, he is depicted in old age, towards the end of his life. During the sixteenth century portraits were often copied from an original model or source. It is likely that both Holbein and the artist of F.45 may have used the same source, now lost, for their representation of the king. F.45 is one of four portraits of the Tudor Royal family that was in Forster's collection. These included portraits of Elizabeth of York (F. 46); Edward VI (F.47); Mary Queen of Scots (F.48) and Forster acquired this painting from the Rev. R. E. Landor (1781-1869). These paintings formed part of Forster's collection of portraits of famous figures from British history. |

| Historical context | In his encyclopaedic work, Historia Naturalis, the ancient Roman author Pliny the Elder described the origins of painting in the outlining of a man's projected shadow in profile. In the ancient period, profile portraits were found primarily in imperial coins. With the rediscovery and the increasing interest in the Antique during the early Renaissance, artists and craftsmen looked back to this ancient tradition and created medals with profile portraits on the obverse and personal devise on the reverse in order to commemorate and celebrate the sitter. Over time these profile portraits were also depicted on panels and canvas, and progressively evolved towards three-quarter and eventually frontal portraits. These portraits differ in many ways from the notion of portraiture commonly held today as they especially aimed to represent an idealised image of the sitter and reflect therefore a different conception of identity. The sitter's likeness was more or less recognisable but his particular status and familiar role were represented in his garments and attributes referring to his character. The 16th century especially developed the ideal of metaphorical and visual attributes through the elaboration of highly complex portrait paintings in many formats including at the end of the century full-length portraiture. It was during the reign of Henry VII that the Portraiture started to flourish in England. This followed the development of the genre in other European Courts. Henry VII commissioned many portraits of himself and his wife. This reflects contemporary interest in Europe in the use of portraiture as a means of royal propaganda. Most of the surviving portraits of the Henry VII were produced in the 16th. These stem from the same composition, showing the king in three-quarter pose, turning to his left or right. This recurring model made the portraits of the King easily recognisable by his subjects. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | F.45 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 7, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest