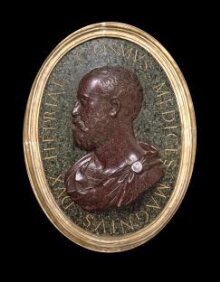

Portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici

Relief

1570 (made)

1570 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The title of Grand Duke was conferred on Cosimo I by Pope Pius V in 1569. The relief is signed and dated under the truncation of the bust: MDLXX/FRANci OPVS/F. Francesco del Tadda became a specialist in the carving of porphyry, and both Tadda and Cosimo I himself are credited in contemporary sources with developing new methods of carving this hardstone. There are porphyry reliefs of other members of the Medici family in the Museon Nazionale del Bargello in Florence.

In sixteenth-century Florence there was a passionate campaign to make the royal and imperial stone of porphyry the special province of the Medici. In fact, Vasari created a script that placed the recovery of the “secret” of producing complex works of sculpture out of the dauntingly hard material of porphyry at the court of Cosimo de’ Medici I. Not only did Cosimo’s interest in porphyry bring it to the fore as a material for the sculptural and architectural production of his reign, but according to Vasari it was Duke Cosimo I himself who directed the manufacture of the herbal essence that made possible the tempering of steel chisels to be hard enough to work the stone.

During the opening phase of the Medici porphyry campaign in the 1550’s, the manual skill was provided by Francesco Ferucci del Tadda, more familiarly known as Tadda. He was a member of the long established Ferrucci family of Fiesole, who were expert stone workers and part-time architects. To work porphyry, Tadda had to contend with technical limitations unknown to most of his professional contemporaries, namely the hardness of the stone and the tools required to shape it; the need for large quantities of it at a time when competition for antique materials had long been keen; and the sheer time it took to carve due to the slow rhythmic pace required. The technique demanded several weeks for an eye, several months for a relief head and over a decade for a large figure in the round.

In sixteenth-century Florence there was a passionate campaign to make the royal and imperial stone of porphyry the special province of the Medici. In fact, Vasari created a script that placed the recovery of the “secret” of producing complex works of sculpture out of the dauntingly hard material of porphyry at the court of Cosimo de’ Medici I. Not only did Cosimo’s interest in porphyry bring it to the fore as a material for the sculptural and architectural production of his reign, but according to Vasari it was Duke Cosimo I himself who directed the manufacture of the herbal essence that made possible the tempering of steel chisels to be hard enough to work the stone.

During the opening phase of the Medici porphyry campaign in the 1550’s, the manual skill was provided by Francesco Ferucci del Tadda, more familiarly known as Tadda. He was a member of the long established Ferrucci family of Fiesole, who were expert stone workers and part-time architects. To work porphyry, Tadda had to contend with technical limitations unknown to most of his professional contemporaries, namely the hardness of the stone and the tools required to shape it; the need for large quantities of it at a time when competition for antique materials had long been keen; and the sheer time it took to carve due to the slow rhythmic pace required. The technique demanded several weeks for an eye, several months for a relief head and over a decade for a large figure in the round.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Porphyry set in serpentine |

| Brief description | Relief, porphyry, portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici, by Francesco di Giovanni Ferrucci (Francesco del Tadda), Florence, 1570. |

| Physical description | Relief in porphyry set on an oval slab of serpentine (verde di Prato). The bust is shown turned three-quarters to the left with the head in profile. Cosimo wears a mantle over armour and fastened at the shoulder with a clasp. Round the edge of the background runs the inscription in incised gilt letters COSMVS MEDICES MAGNIVS DVX HETRVRIAE. In an oval moulded frame of white marble with faint traces of gilding. The frame is in four sections. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Limited edition |

| Marks and inscriptions | MDLXX/FRANci OPVS/F Note Signed beneath the truncation of the bust alongside a makers mark Translation 1570/ |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This relief was acquired in Florence in 1864 together with an eighteenth-century sedan chair used by the the Medici Grand Dukes (10-1864). Four years earlier Tuscany had been annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia, and from 1861 Victor Emmanuel ruled in Florence as King. At such a time it is likely that many opportunities arose where objects from the Medici collections came onto the market, and this relief, although heavy, is not unmanageably bulky. Historical significance: Tadda’s series of low relief Medici portraits, such as this example, demonstrate how he exercised his design sense, and illustrate the artistic goals he set for himself as a porphyry carver. In 1570, a year after Cosimo I was conferred the title of Grand Duke, Tadda completed this relief portrait of him, carving his own name boldly into its truncation. His signature suggests that he hoped to associate himself with the fame of Duke Cosimo and indicates the pride he took in the relief’s technical and design merits. Like cameo-carvers who maximised the irregularities of shape and colouring in their stone, Tadda has exploited the contour and thickness of this particular porphyry fragment to accentuate specific features and create the kind of high relief effects favoured by medallists (See Pope-Hennessy, 1964). By setting the strong shape of Cosimo’s overmantle at an angle to the ground and balancing it below with a strongly projecting truncation, he creates a sense of containment for the profile and relates the whole head nicely to its oval ground. But, in adapting the design details to the structural idiosyncrasies of the stone, he employed very specific tools and embarked on new ways of varying the surface texture. Unlike carvers and sculptors, who would have used points and claw chisels, Tadda used picchierelli (tiny steel hammers sharpened to fine points) to work the porphyry in its early stages, and then flat chisels when it came to the final skin of his works. Under a raking light, the smooth surfaces of this portrait can be seen in parts to be covered by a series of parallel striations, following the typography of Cosimo’s face and neck (see Butters, 1996). Far from being irregular signs of abrasion, these seem to be the trails of tiny chisels struck edge-on. Equally, just as the claw chisels used by sculptors produced ridges in softer marbles which were then smoothed away with flat chisels, so it can be observed that Cosimo’s drapery folds began as ridges which Tadda then modelled with his scarpelletti, as he did on Cosimo’s face and neck. In order to achieve the final polish of the stone, Tadda must have worked with fine abrasives and polishing powders, rather than the rasps and files that sculptors used, which would have been weakened by hard tempering. |

| Historical context | In sixteenth-century Florence there was a passionate campaign to make the royal and imperial stone of porphyry the special province of the Medici. In fact, Vasari created a script that placed the recovery of the “secret” of producing complex works of sculpture out of the dauntingly hard material of porphyry at the court of Cosimo de’ Medici I. Not only did Cosimo’s interest in porphyry bring it to the fore as a material for the sculptural and architectural production of his reign, but according to Vasari it was Duke Cosimo I himself who directed the manufacture of the herbal essence that made possible the tempering of steel chisels to be hard enough to work the stone. During the opening phase of the Medici porphyry campaign in the 1550’s, the manual skill was provided by Francesco Ferucci del Tadda, more familiarly known as Tadda. He was a member of the long established Ferrucci family of Fiesole, who were expert stone workers and part-time architects. To work porphyry, Tadda had to contend with technical limitations unknown to most of his professional contemporaries, namely the hardness of the stone and the tools required to shape it; the need for large quantities of it at a time when competition for antique materials had long been keen; and the sheer time it took to carve due to the slow rhythmic pace required. With a technique that demanded several weeks for an eye, several months for a relief head and over a decade for a large figure in the round, Tadda and his workshop managed to produce a least twenty works of varying sizes for his ducal patrons, two for himself and a variety of works now lost (see Butters, 1996). While a good carver was not expected to design his own works and often based portraits on those by previous sculptors, painters and medallists, Tadda’s acceptance to the Academy of Design is a sure indication that he was not entirely lacking in disegno. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | The title of Grand Duke was conferred on Cosimo I by Pope Pius V in 1569. The relief is signed and dated under the truncation of the bust: MDLXX/FRANci OPVS/F. Francesco del Tadda became a specialist in the carving of porphyry, and both Tadda and Cosimo I himself are credited in contemporary sources with developing new methods of carving this hardstone. There are porphyry reliefs of other members of the Medici family in the Museon Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. In sixteenth-century Florence there was a passionate campaign to make the royal and imperial stone of porphyry the special province of the Medici. In fact, Vasari created a script that placed the recovery of the “secret” of producing complex works of sculpture out of the dauntingly hard material of porphyry at the court of Cosimo de’ Medici I. Not only did Cosimo’s interest in porphyry bring it to the fore as a material for the sculptural and architectural production of his reign, but according to Vasari it was Duke Cosimo I himself who directed the manufacture of the herbal essence that made possible the tempering of steel chisels to be hard enough to work the stone. During the opening phase of the Medici porphyry campaign in the 1550’s, the manual skill was provided by Francesco Ferucci del Tadda, more familiarly known as Tadda. He was a member of the long established Ferrucci family of Fiesole, who were expert stone workers and part-time architects. To work porphyry, Tadda had to contend with technical limitations unknown to most of his professional contemporaries, namely the hardness of the stone and the tools required to shape it; the need for large quantities of it at a time when competition for antique materials had long been keen; and the sheer time it took to carve due to the slow rhythmic pace required. The technique demanded several weeks for an eye, several months for a relief head and over a decade for a large figure in the round. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 1-1864 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 20, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest