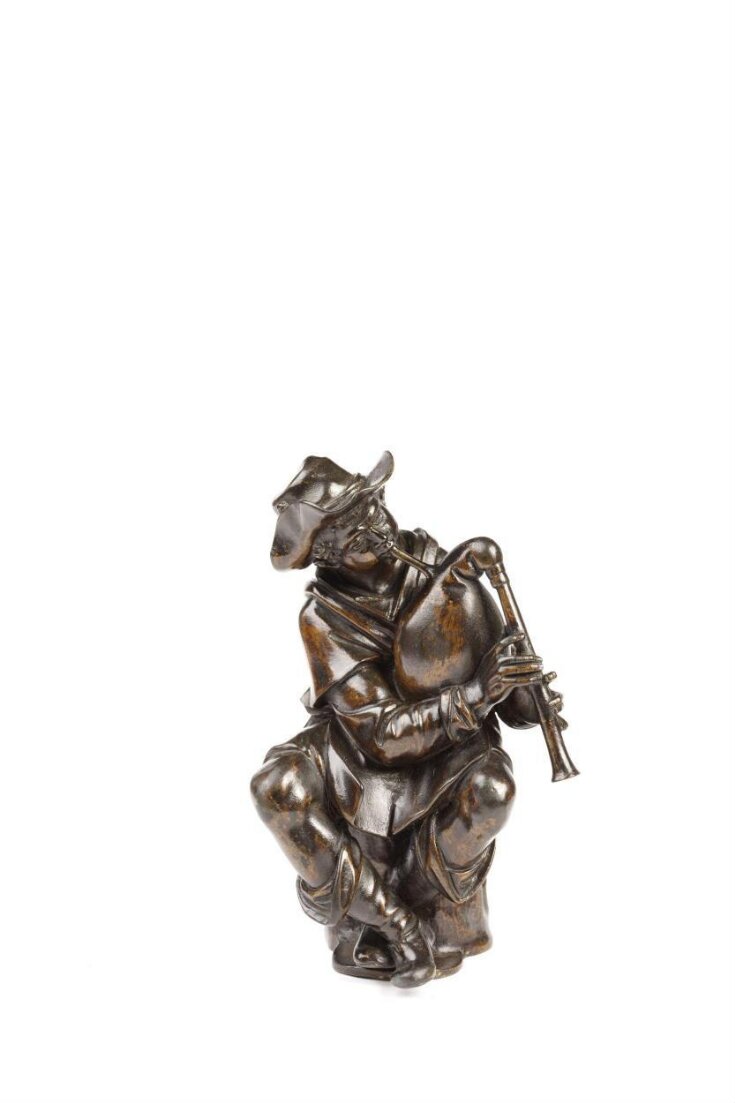

Seated boy playing the bagpipes

Statuette

1590-1610 (made)

1590-1610 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

It is known that a statuette of a Bagpiper was sent to Henry, Prince of Wales, in England in 1611 as a gift from the Medici during unsuccessful negotiations of a marriage contract. The motif is derived from an engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) dated 1514 and is generally accepted as a model by Giambologna or a close follower such as his assistant and successor as sculptor to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Pietro Tacca (1577-1640). Bronze statuettes such as this, were highly sought after by collectors at this time because they often provided smaller versions of large statues and coincided with an upsurge of interest in classical antiquity.

The poetic quality of this type of pastoral genre model clearly appealed to collectors at the time. Indeed, the model’s similarity to Dürer’s engraving of 1514 (currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which shows a standing, cross-legged Bagpiper, suggests that Giambologna perhaps owned a copy of the print. A tradition of such genre figures may already have been established north of the Alps before there was one in Italy.

The poetic quality of this type of pastoral genre model clearly appealed to collectors at the time. Indeed, the model’s similarity to Dürer’s engraving of 1514 (currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which shows a standing, cross-legged Bagpiper, suggests that Giambologna perhaps owned a copy of the print. A tradition of such genre figures may already have been established north of the Alps before there was one in Italy.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Seated boy playing the bagpipes (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Bronze |

| Brief description | Statuette, bronze, a seated boy playing the bagpipes, after a model by Giambologna, Italy (Florence), ca. 1590-1610 |

| Physical description | Bronze statuette of a seated boy playing the bagpipes. He wears a loose smock and a wide-brimmed hat and sits on the stump of a tree trunk with his body turned to the right and his legs crossed so that the bagpipes rest on his right leg. Brown-orange natural patina, as seen on many Florentine bronzes of this period. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Unique |

| Gallery label | |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by Dr W. L. Hildburgh |

| Object history | This object was bequeathed in 1956 by Dr W.L. Hildburgh FSA. Historical significance: The model for the Seated Bagpiper was one of Giambologna’s most popular designs and was not only copied in bronze and ivory but also inspired many figures subsequently made in porcelain. The bronze reproductions, in particular, fall into two categories. There are rough casts, like that in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and the Wernher Collection, formerly located in Bedfordshire (and now on loan to Ranger's House) which are generally crude in their detailing and display minor variations such as no mouthpiece to the bagpipe, the hat being of slightly different shape, or the horn missing from below the figure’s left hand. Yet while such versions are clearly inferior derivatives, they nonetheless have considerable character. This particular reproduction, falls into the second category, which display far finer finish and surface delicacy. The diverging line in the folds of the tops of the boots, and the crisp hard angles of the drapery, which in some cases form curvilinear shapes, are greatly refined. With a higher level of chasing, details extend to a texturing of the hair and tree stump, and more expressive facial features, making it of notable quality. Given their almost identical size and complex interplay of angular forms, it is plausible that this statuette along with those in the Palazzo Venezia, the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, and the Fitzwilliam Museum are all from the workshop of Giambologna. This particular version has been attributed by Radcliffe to Pietro Tacca (1577-1640), one of Giambologna's assistants and successor as sculptor to the Grand Duke of Tuscany. |

| Historical context | The first reliable reference to the bagpiper appears in a bill of lading in March 1611, recording a number of bronze statuettes shipped to England as diplomatic gifts from Cosimo II de’ Medici to Prince Henry of Wales: ”Uno Pastore che suona la Piva” (see Watson and Avery 1973). However, the model was possibly that referred to in a document of 1601 where it is described as “a silver figurine of a shepherd weighing 11.8 ounces” (approx. 0.334kg) but with no mention of bagpipes: “Une figuretta d’Arg(en)to di Pastore…pesc on. 11.8” (see Guardaroba Medicea Vol. 208). Relating to the Bagpiper, and also appearing on the 1611 list of bronzes sent to England, was a peasant resting on a staff - Uno Villiano che s’appoggia a uno bastone”. Given the pose, showing the figure looking down, it has been suggested that these two figures may have been designed as a pair with the standing peasant listening to the seated performer. Significantly, the lists of 1601 and 1611 are closely linked. The first, relating to four silver statuettes in the Galleria of the Uffizi, were sent out on loan by the Grand Duke to Antonio Susini, Giambologna’s most talented Florentine assistant. These models were then reproduced in bronze, presumably in multiple copies given the number of existing versions, and a number were then sent to England, as noted in 1611. The models of the silver figures are doubtless by Giambologna, and in the inventory of Benedetto Gondi in 1609, for example, it states that the sculptor made at least one Pastorino. Moreover, they relate in theme to much of the garden statuary made for Francesco I de’ Medici’s villa at Pratolino, near Forence, much of which was designed by Giambologna. The poetic quality of this type of pastoral genre model clearly appealed to collectors at the time. Indeed, the model’s similarity to Dürer’s engraving of 1514 (currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which shows a standing, cross-legged Bagpiper, suggests that Giambologna perhaps owned a copy of the print. A tradition of such genre figures may already have been established north of the Alps before there was one in Italy. A Bagpiper featured in the inventory of an Antwerp collector N.C.Cheus (1621): "een (figure) van moesler oft ruyspyper" (see Denucé, 1932) |

| Production | after Giambologna |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | It is known that a statuette of a Bagpiper was sent to Henry, Prince of Wales, in England in 1611 as a gift from the Medici during unsuccessful negotiations of a marriage contract. The motif is derived from an engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) dated 1514 and is generally accepted as a model by Giambologna or a close follower such as his assistant and successor as sculptor to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Pietro Tacca (1577-1640). Bronze statuettes such as this, were highly sought after by collectors at this time because they often provided smaller versions of large statues and coincided with an upsurge of interest in classical antiquity. The poetic quality of this type of pastoral genre model clearly appealed to collectors at the time. Indeed, the model’s similarity to Dürer’s engraving of 1514 (currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which shows a standing, cross-legged Bagpiper, suggests that Giambologna perhaps owned a copy of the print. A tradition of such genre figures may already have been established north of the Alps before there was one in Italy. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.59-1956 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 30, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest