Mortar

ca. 1540 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Mortars and pestles were used for centuries to grind and mix substances used in medicine, alchemy, cosmetics, cooking and gunpowder manufacture. Craftsmen including painters and goldsmiths also used them to reduce materials to powder form.

During the 16th century, mortars and pestles were standard domestic utensils. They were used daily in the preparation of food. Herbs and spices, loaves of sugar, grains and other ingredients were virtually all of supplied whole until the 18th century and ground in the home. Mortars were also used for grinding soaps and for the preparation of perfumes.

Mortars and pestles were also standard tools of the trade for physicians and apothecaries. The French physician Philbert Guibert stated in his Le Medecin Charitable (1625) that it was "... necessary to furnish an Apothecary [with] ... a great Morter of Brass weighing fifty of sixty pound or more, with a pestle of iron,. A little Morter weighing five or six pounds with a pestle of the same matter. A middle sized Morter of Marble, and a pestle of wood, and a stone morter with the same pestle."

Apothecaries were distrusted by some scientific writers. The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) criticised the trend of apothecaries replacing doctors in the preparation of medicines: "... as long as there are apothecaries and mortars, there is no art in medicine other than child's play, confusion, and drunken revelry."

Most families of middle wealth or above produced their own drugs and medicines in various forms. Larger households possessed several mortars for preparing potions and remedies. The modern garden evolved from the plots outside larger households in which grew the life preserving herbs and flowers used in medicine.

Mortars were also associated with alchemy, the quest to turn base metals into gold. Mortars were deemed to have special properties: in them one might discover the secret of life.

During the 16th century, mortars and pestles were standard domestic utensils. They were used daily in the preparation of food. Herbs and spices, loaves of sugar, grains and other ingredients were virtually all of supplied whole until the 18th century and ground in the home. Mortars were also used for grinding soaps and for the preparation of perfumes.

Mortars and pestles were also standard tools of the trade for physicians and apothecaries. The French physician Philbert Guibert stated in his Le Medecin Charitable (1625) that it was "... necessary to furnish an Apothecary [with] ... a great Morter of Brass weighing fifty of sixty pound or more, with a pestle of iron,. A little Morter weighing five or six pounds with a pestle of the same matter. A middle sized Morter of Marble, and a pestle of wood, and a stone morter with the same pestle."

Apothecaries were distrusted by some scientific writers. The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) criticised the trend of apothecaries replacing doctors in the preparation of medicines: "... as long as there are apothecaries and mortars, there is no art in medicine other than child's play, confusion, and drunken revelry."

Most families of middle wealth or above produced their own drugs and medicines in various forms. Larger households possessed several mortars for preparing potions and remedies. The modern garden evolved from the plots outside larger households in which grew the life preserving herbs and flowers used in medicine.

Mortars were also associated with alchemy, the quest to turn base metals into gold. Mortars were deemed to have special properties: in them one might discover the secret of life.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Copper-alloy (probably bronze), cast |

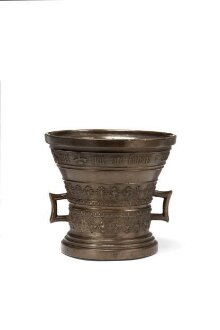

| Brief description | Bronze, Netherlands, around 1540, bucket shaped with horizontal fluted bands, Gothic foliage and inscription. |

| Physical description | Bucket-shaped bronze mortar, probably cast in a bell-mould, with flat, circular, stepped base and convex sides, the lower body with two opposing bands of running floral ornament, separated by a fluted horizontal band. This fluted band is repeated above the upper floral band. The mortar has a flared top with thicker gauge metal at the lip. The mortar base has a pronounced sprue mark in the centre where the molten copper alloy was poured into the mould and then filed off after casting. The mortar has two handles, each formed as three sides of a rectangle but with concave lines. An inscription in cast Gothic script runs below the rim. There are various dents and nicks in the surface of the mortar and patches of later lead soldering fill areas of pitting on the base. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Credit line | Given by Dr W.L. Hildburgh |

| Object history | The history of this mortar prior to its gift to the Museum is unknown. The mortar was given to the Museum in 1938 by Dr Walter Leo Hildburgh. Hildburgh was one of the V&A's most dedicated and generous patrons. Born in New York in 1876, he trained as a scientist. Initially he collected ethnography but after 1914 he turned to the decorative arts. Encouraged by successive Keepers of Metalwork, he accumulated huge collections of Spanish and German metalwork. From 1924 when he first offered objects to the Museum on loan, to 1956 when he bequeathed his huge collection, Hildburgh was part of the Museum landscape. He regularly gave the Museum presents at Christmas and on his birthday. His will set up a fund for future purchases, administered in the spirit of his earlier acquisitions. Historical significance: This mortar is of exceptional quality. The casting is crisp and most of the decorative elements are in excellent condition. In style it straddles the Gothic and the Renaissance. The two friezes of running foliage resemble architectural mouldings of the 15th century. The shape of the mortar, however, with its strong horizontal banding and wide flared lip, is typical of the mid 16th century. It appears that a mixture of old and new moulds have been used in the manufacture of the mortar. |

| Historical context | The word 'mortar' evolved from the Latin mortarium and possibly derives from mordeo meaning to bite. This in turn may relate to the Sanskrit mrdi meaning to grind or pound. (Motture, p.37) Mortars and pestles were used for centuries to grind and mix substances used in medicine, alchemy, cosmetics, cooking and gunpowder manufacture. Craftsmen including painters and goldsmiths also used them to reduce materials to powder form. Copper based mortars and pestles were used particularly for grinding hard substances such as barks, resins, and spices. Marble mortars were recommended for powdery and dry materials, and pills and potions were often ground in glass. The smallest mortars were not much larger than thimbles and may have been used more as display pieces that functional items. Some mortars were over 50 cm high and were extremely heavy. Their accompanying pestles might be suspended from a counter spring which took some of the weight. The basic bucket shape of mortars was established by the 16th century, with the diameter of its opening about half as large again as the internal diameter of the base and its height roughly equivalent to the larger diameter at the top. They replaced the tall, slender mortars of the 15th century, with their vertical ribbed bands and (sometimes) figural feet. The new mortars originated in Italy and demonstrated strong horizontal planes displaying friezes and inscriptions. Inscriptions bearing the owners’ names were quite common and sometimes, as with this example, record the maker’s name. Motifs for decorating mortars and bells during the 16th century included running foliage, imaginary creatures, animals and stylised heads. Sometimes symbols gave a hint of the function of the mortar. The fashion for highly decorated mortars continued until the mid 17th century when plain surfaces returned. Mortars became purely functional. By the 18th century their use declined as commercial grinding machines became more common. Metal mortars declined in particular as there was also an increased awareness of the dangers of using copper based materials for preparing food. During the 16th century, mortars and pestles were standard domestic utensils. They were used daily in the preparation of food. As exploration opened up new territories and supply routes, new spices were imported from the East and the New World. Herbs and spices, loaves of sugar, grains and other ingredients were virtually all supplied whole until the 18th century and ground in the home. Mortars were also used for grinding soaps and for the preparation of perfumes. Before 1500 it was customary for wealthy merchants and aristocrats to give their new daughters-in-law a mortar as a wedding present. Mortars and pestles were also standard tools of the trade for physicians and apothecaries. The French physician Philbert Guibert stated in his Le Medecin Charitable (1625) that it was "... necessary to furnish an Apothecary [with] ... a great Morter of Brass weighing fifty of sixty pound or more, with a pestle of iron,. A little Morter weighing five or six pounds with a pestle of the same matter. A middle sized Morter of Marble, and a pestle of wood, and a stone morter with the same pestle." Apothecaries were distrusted by some scientific writers. The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) criticised the trend of apothecaries replacing doctors in the preparation of medicines: "Thus the apothecaries arose, and as long as there are apothecaries and mortars, there is no art in medicine other than child's play, confusion, and drunken revelry." (quoted from Pagel, Walter, 'Vesalius and Paracelsus' in Winder, Marianne ed., From Paracelsus to Van Helmont: Studies in Renaissance Science, London 1986, p. 322) Most families of middle wealth or above produced their own drugs and medicines in various forms. Larger households possessed several mortars for preparing potions and remedies. The modern garden evolved from the plots outside larger households in which grew the life preserving herbs and flowers used in medicine. Mortars were also associated with alchemy, the quest to turn base metals into gold. Alchemy was an experimental science and philosophy which sought to understand transformation and the relationship between people and their surroundings. Mortars were deemed to have special properties: in them one might discover the secret of life. |

| Production | Elements cast in the same moulds as 2716-1855 |

| Summary | Mortars and pestles were used for centuries to grind and mix substances used in medicine, alchemy, cosmetics, cooking and gunpowder manufacture. Craftsmen including painters and goldsmiths also used them to reduce materials to powder form. During the 16th century, mortars and pestles were standard domestic utensils. They were used daily in the preparation of food. Herbs and spices, loaves of sugar, grains and other ingredients were virtually all of supplied whole until the 18th century and ground in the home. Mortars were also used for grinding soaps and for the preparation of perfumes. Mortars and pestles were also standard tools of the trade for physicians and apothecaries. The French physician Philbert Guibert stated in his Le Medecin Charitable (1625) that it was "... necessary to furnish an Apothecary [with] ... a great Morter of Brass weighing fifty of sixty pound or more, with a pestle of iron,. A little Morter weighing five or six pounds with a pestle of the same matter. A middle sized Morter of Marble, and a pestle of wood, and a stone morter with the same pestle." Apothecaries were distrusted by some scientific writers. The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) criticised the trend of apothecaries replacing doctors in the preparation of medicines: "... as long as there are apothecaries and mortars, there is no art in medicine other than child's play, confusion, and drunken revelry." Most families of middle wealth or above produced their own drugs and medicines in various forms. Larger households possessed several mortars for preparing potions and remedies. The modern garden evolved from the plots outside larger households in which grew the life preserving herbs and flowers used in medicine. Mortars were also associated with alchemy, the quest to turn base metals into gold. Mortars were deemed to have special properties: in them one might discover the secret of life. |

| Associated object | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.7-1938 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 3, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest