Dish

ca. 1515 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Decoration of this sort, known as grotteschi, became fashionable in Renaissance Italy following the discovery in Rome, in about 1480, of the so-called Golden Palace of the Emperor Nero. The excavated chambers contained perfectly preserved wall and ceiling paintings, comprising fantastical creatures, ribbons and festoons. These ornaments provided artists of all kinds with a rich source of inspiration. The almost infinite possibilities of design gave them the means to fulfil the desires of the Renaissance market for beauty, abundance, caprice and wit.

Ovid's Metamorphoses, recounting lively tales from Classical mythology, was much used by Renaissance artists. In 1497 a Venetian printer, Zoane Rosso, published a new edition of the text accompanied by allegorical interpretations and illustrative woodcuts that became essential sources for maiolica painters. The first Italian translation was printed in 1522, which greatly increased the popularity of Ovid and set the precedent for further translations into the vernacular. Ovid was extremely important to the humanistic tradition of the Renaissance, and was studied alongside Circero, Horace and Virgil.

According to the Greek myth, Leda was approached by the god Zeus, masquerading as a swan, and the subsequent union resulted in the birth of Helen, who later became the wife of Theseus, King of Athens, and renowned for her very great beauty.

The story of Leda conformed very neatly with the importance of dynastic fulfilment and the continuation of a noble lineage in Renaissance society. Such a plate would have been admired not just for its beauty and erudition in recalling episodes from classical mythology but may also have appealed to the Renaissance inclination to the erotic. Indeed, numerous plates bearing such mythical or allegorical themes lifted their subjects directly from such sources as Giulio Romano's I modi, the notorious erotic prints illustrative of various sexual positions.

The figure of Fortune is adapted from an engraving by Nicoletto da Modena; it differs from its source in the position of the left arm and the elimination of all accessories. The whole composition of the design is strongly reminiscent of the panels of grotesques by the same engraver.

The fan-like flowers on the back are a peculiarity of Cafaggiolo.

Ovid's Metamorphoses, recounting lively tales from Classical mythology, was much used by Renaissance artists. In 1497 a Venetian printer, Zoane Rosso, published a new edition of the text accompanied by allegorical interpretations and illustrative woodcuts that became essential sources for maiolica painters. The first Italian translation was printed in 1522, which greatly increased the popularity of Ovid and set the precedent for further translations into the vernacular. Ovid was extremely important to the humanistic tradition of the Renaissance, and was studied alongside Circero, Horace and Virgil.

According to the Greek myth, Leda was approached by the god Zeus, masquerading as a swan, and the subsequent union resulted in the birth of Helen, who later became the wife of Theseus, King of Athens, and renowned for her very great beauty.

The story of Leda conformed very neatly with the importance of dynastic fulfilment and the continuation of a noble lineage in Renaissance society. Such a plate would have been admired not just for its beauty and erudition in recalling episodes from classical mythology but may also have appealed to the Renaissance inclination to the erotic. Indeed, numerous plates bearing such mythical or allegorical themes lifted their subjects directly from such sources as Giulio Romano's I modi, the notorious erotic prints illustrative of various sexual positions.

The figure of Fortune is adapted from an engraving by Nicoletto da Modena; it differs from its source in the position of the left arm and the elimination of all accessories. The whole composition of the design is strongly reminiscent of the panels of grotesques by the same engraver.

The fan-like flowers on the back are a peculiarity of Cafaggiolo.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Tin-glazed earthenware |

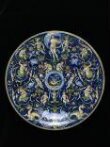

| Brief description | Dish with grotesques and central medallion depicting Leda and the Swan, probably painted by Jacopo, Cafaggiolo, ca. 1515. |

| Physical description | Dish. Painted with a grotesque composition covering the whole surface. In the middle, in a medallion flanked by ram's heads, Leda and the Swan, with the name LEDA on a tablet. Above the medallion, between two crouching boys holding cornucopias, springs a flower supporting a figure of Fortune. The back is painted in blue with stylized flowers ('mezzaluna dentata') motifs on scrolled stems on the rim and the monograph SP in the middle. Colours are blue, orange, yellow, green and red. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 'SP' (monogram on the reverse

Sticky label: HUNEGG) |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by George Salting, Esq. |

| Object history | Formerly part of the Parpart and Spitzer Collections Historical significance: According to the Greek myth, Leda was approached by the god Zeus, masquerading as a swan, and the subsequent union resulted in the birth of Helen, who later became the wife of Theseus, King of Athens, and renowned for her very great beauty. The story of Leda conformed very neatly with the importance of dynastic fulfilment and the continuation of a noble lineage in Renaissance society. Such a plate would have been admired not just for its beauty and erudition in recalling episodes from classical mythology but may also have appealed to the Renaissance inclination to the erotic. Indeed, numerous plates bearing such mythical or allegorical themes lifted their subjects directly from such sources as Giulio Romano's I modi, the notorious erotic prints illustrative of various sexual positions. The figure of Fortune is adapted from an engraving by Nicoletto da Modena; it differs from its source in the position of the left arm and the elimination of all accessories. The whole composition of the design is strongly reminiscent of the panels of grotesques by the same engraver. The fan-like motifs on the back, called 'mezzaluna dentata' are typical features of Caffaggiolo production. |

| Historical context | Decoration of this sort, known as grottesche, became fashionable in Renaissance Italy following the discovery in Rome, in about 1480, of the so-called Golden Palace of the Emperor Nero. The excavated chambers contained perfectly preserved wall and ceiling paintings, comprising fantastical creatures, ribbons and festoons. These ornaments provided artists of all kinds with a rich source of inspiration. The almost infinite possibilities of design gave them the means to fulfil the desires of the Renaissance market for beauty, abundance, caprice and wit. Ovid's Metamorphoses, recounting lively tales from Classical mythology, was much used by Renaissance artists. In 1497 a Venetian printer, Zoane Rosso, published a new edition of the text accompanied by allegorical interpretations and illustrative woodcuts that became essential sources for maiolica painters. The first Italian translation was printed in 1522, which greatly increased the popularity of Ovid and set the precedent for further translations into the vernacular. Ovid was extremely important to the humanistic tradition of the Renaissance, and was studied alongside Circero, Horace and Virgil. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Decoration of this sort, known as grotteschi, became fashionable in Renaissance Italy following the discovery in Rome, in about 1480, of the so-called Golden Palace of the Emperor Nero. The excavated chambers contained perfectly preserved wall and ceiling paintings, comprising fantastical creatures, ribbons and festoons. These ornaments provided artists of all kinds with a rich source of inspiration. The almost infinite possibilities of design gave them the means to fulfil the desires of the Renaissance market for beauty, abundance, caprice and wit. Ovid's Metamorphoses, recounting lively tales from Classical mythology, was much used by Renaissance artists. In 1497 a Venetian printer, Zoane Rosso, published a new edition of the text accompanied by allegorical interpretations and illustrative woodcuts that became essential sources for maiolica painters. The first Italian translation was printed in 1522, which greatly increased the popularity of Ovid and set the precedent for further translations into the vernacular. Ovid was extremely important to the humanistic tradition of the Renaissance, and was studied alongside Circero, Horace and Virgil. According to the Greek myth, Leda was approached by the god Zeus, masquerading as a swan, and the subsequent union resulted in the birth of Helen, who later became the wife of Theseus, King of Athens, and renowned for her very great beauty. The story of Leda conformed very neatly with the importance of dynastic fulfilment and the continuation of a noble lineage in Renaissance society. Such a plate would have been admired not just for its beauty and erudition in recalling episodes from classical mythology but may also have appealed to the Renaissance inclination to the erotic. Indeed, numerous plates bearing such mythical or allegorical themes lifted their subjects directly from such sources as Giulio Romano's I modi, the notorious erotic prints illustrative of various sexual positions. The figure of Fortune is adapted from an engraving by Nicoletto da Modena; it differs from its source in the position of the left arm and the elimination of all accessories. The whole composition of the design is strongly reminiscent of the panels of grotesques by the same engraver. The fan-like flowers on the back are a peculiarity of Cafaggiolo. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Other number | 310 - Rackham (1977) |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.2153-1910 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 3, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest