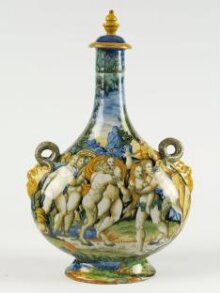

Pilgrim Bottle

ca. 1550 (made)

| Place of origin |

During the sixteenth century the diet of the elite expanded. New ingredients were available from a widening global market and lavish recipes proliferated in the period. For the first time, gastronomic literature became part of the food culture of the wealthy. What was eaten and drunk mattered as it reflected and constructed an individual's social status. New ceramic forms for holding the growing variety of types of foodstuffs and for accommodating the stylish modes of eating were developed; such as crespine (moulded dishes for holding fruit), piatte detti da carne (meat plates) and rinfrescatoio (coolers). Knowledge of the specific functions of the new forms also formed part of the self-conscious preoccupation with discernment and decorum. During the century a number of codified philosophical ideas on manners, cleanliness and hospitality that reflected this concern were written. The production of clear glass (cristallino) tazze from Murano is a good example of the self-conscious interest in fine manners. The shape of the glass made drinking difficult, it demanded due attention to avoid spillage.

The introduction of individual vessels, cutlery, napkins, tablecloths and place settings at table also signaled a development in the elite modes of eating and drinking. It marked a change with the earlier medieval practice of sharing implements. For the first time dining "services" were produced with individual flatware or plates for those at table. Sets were produced in standard quantities, plates were sold in by six or twelve. As luxury items, however maiolica services were however also specially commissioned and often decorated with the appropriate heraldic devices and imprese linking the individual service with the patron. However, it is likely that these items were reserved for occasional use or display purposes only.

From the end of the fifteenth century maiolicaware was often painted with antique narratives known as "istoriato". The depiction of these ancient myths and histories, painted in perspective, echoed the intellectual interests of the period. Indeed, the idea behind such decoration on vessels for eating and drinking may have been that guests would have been able to recognize the stories and characters, which reflected on and flattered their classical learning and erudition.

The introduction of individual vessels, cutlery, napkins, tablecloths and place settings at table also signaled a development in the elite modes of eating and drinking. It marked a change with the earlier medieval practice of sharing implements. For the first time dining "services" were produced with individual flatware or plates for those at table. Sets were produced in standard quantities, plates were sold in by six or twelve. As luxury items, however maiolica services were however also specially commissioned and often decorated with the appropriate heraldic devices and imprese linking the individual service with the patron. However, it is likely that these items were reserved for occasional use or display purposes only.

From the end of the fifteenth century maiolicaware was often painted with antique narratives known as "istoriato". The depiction of these ancient myths and histories, painted in perspective, echoed the intellectual interests of the period. Indeed, the idea behind such decoration on vessels for eating and drinking may have been that guests would have been able to recognize the stories and characters, which reflected on and flattered their classical learning and erudition.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Tin-glazed earthenware |

| Brief description | Pilgrim bottle decorated with bacchanalian scenes, possibly by Francesco Durantino, Urbino, ca. 1550. |

| Physical description | Pilgrim bottle with screw stopper and two moulded stayr's mask handles. Manganese purple added to the usual palette. The whole surface is covered with bacchanalian scenes in a continuous landscape. On one side Bacchus, vine-crowned, sits amongst a crowd of reveling satyrs, bacchantes and children, with Cupid astride a goat; on the other, a party of bacchantes being assaulted by two satrys. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Bequeathed by George Salting, Esq. |

| Object history | Historical significance: From the end of the fifteenth century maiolica was often painted with antique narratives known as "istoriato". The depiction of these ancient myths and histories, painted in perspective, echoed the intellectual interests of the period. Indeed, the idea behind such decoration on vessels for eating and drinking may have been that guests would have been able to recognize the stories and characters, which reflected on and flattered their classical learning and erudition. The form of the pilgrim bottle had been in existence since the eleventh century. However, in this example, the original function, that of carrying water on journeys, would have no longer applied. Nevertheless, the shape of the bottle allowed for innovative design that often enabled the narrative to move around the vessel. It is a form well suited for a depicted of Bacchanalian revelers. (on C2299-1910 for the story of the rape of Europa). It is possible that this bottle would have formed part of the display on a credenza. |

| Historical context | During the sixteenth century the diet of the elite expanded. New ingredients were available from a widening global market and lavish recipes proliferated in the period. For the first time, gastronomic literature became part of the food culture of the wealthy. A number of codified philosophical ideas on manners, cleanliness and hospitality were written revealing a broader preoccupation with behaviour and social status. The introduction of individual vessels, cutlery, napkins, tablecloths and place settings at table also signaled a development in the elite modes of eating and drinking. It marked a change with the earlier medieval practice of sharing eating implements. For the first time dining "services" were produced with individual flatware or plates for those at table. Sets were produced in standard quantities, plates were sold by six or twelve. Clear glass known as cristallino which was often enameled and gilded, produced in Murano, became desirable for drinking vessels. There is evidence to suggest that fine maiolica services may have been displayed on the credenza in the same manner as silver. |

| Production | The attribution to Francesco Durantino is somewhat uncertain, the painting being more careful than many of his works |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | During the sixteenth century the diet of the elite expanded. New ingredients were available from a widening global market and lavish recipes proliferated in the period. For the first time, gastronomic literature became part of the food culture of the wealthy. What was eaten and drunk mattered as it reflected and constructed an individual's social status. New ceramic forms for holding the growing variety of types of foodstuffs and for accommodating the stylish modes of eating were developed; such as crespine (moulded dishes for holding fruit), piatte detti da carne (meat plates) and rinfrescatoio (coolers). Knowledge of the specific functions of the new forms also formed part of the self-conscious preoccupation with discernment and decorum. During the century a number of codified philosophical ideas on manners, cleanliness and hospitality that reflected this concern were written. The production of clear glass (cristallino) tazze from Murano is a good example of the self-conscious interest in fine manners. The shape of the glass made drinking difficult, it demanded due attention to avoid spillage. The introduction of individual vessels, cutlery, napkins, tablecloths and place settings at table also signaled a development in the elite modes of eating and drinking. It marked a change with the earlier medieval practice of sharing implements. For the first time dining "services" were produced with individual flatware or plates for those at table. Sets were produced in standard quantities, plates were sold in by six or twelve. As luxury items, however maiolica services were however also specially commissioned and often decorated with the appropriate heraldic devices and imprese linking the individual service with the patron. However, it is likely that these items were reserved for occasional use or display purposes only. From the end of the fifteenth century maiolicaware was often painted with antique narratives known as "istoriato". The depiction of these ancient myths and histories, painted in perspective, echoed the intellectual interests of the period. Indeed, the idea behind such decoration on vessels for eating and drinking may have been that guests would have been able to recognize the stories and characters, which reflected on and flattered their classical learning and erudition. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.2297&A-1910 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 3, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest