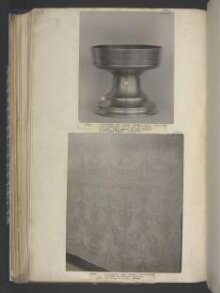

Font Cup

Cup

1500-1520 (made)

1500-1520 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This plain copper alloy cup, orginally gilded, imitates silver-gilt versions and is, in its form, a standing bowl, which would originally have had a cover. Throughout the Middle ages and into the Renaissance, prestige lay in the ownership and display of gold and silver drinking vessels.Large cups like this were used on formal occasions for ceremonial toasts and thanksgiving, and were displayed on buffets when not in use. Cups might be treasured as heirlooms, which accounts for many that survive. At banquets, cups marked the status of the chief guest and the drinking of wine was generally a ritualised ceremony.

This cup, in the form of a standing bowl, would originally have had a cover.This shape of cup seems to appear around 1500, and was known as a 'flatpece'. Its shallow wide bowl and robust, simple design has led such cups to be referred to in modern literature as 'font cups'. By the mid-16th century the shape had evolved into the shallow bowls popular in much of northern Europe. A number of font cups were later used in English churches as communion cups and patens.

This cup is of gilt copper alloy, although much of the gilding has been rubbed away. Traces survive under the trumpet shaped foot. The gilding was applied using the dangerous technique of mercury gilding: a mixture of gold powder and mercury was mixed into a paste and painted onto the surface before the mercury was burned off. Ordinances issued by the Goldsmiths' Company of London in the late 14th century forbade the gilding of base metal objects that might be passed off as gold but this was often ignored.

This cup, in the form of a standing bowl, would originally have had a cover.This shape of cup seems to appear around 1500, and was known as a 'flatpece'. Its shallow wide bowl and robust, simple design has led such cups to be referred to in modern literature as 'font cups'. By the mid-16th century the shape had evolved into the shallow bowls popular in much of northern Europe. A number of font cups were later used in English churches as communion cups and patens.

This cup is of gilt copper alloy, although much of the gilding has been rubbed away. Traces survive under the trumpet shaped foot. The gilding was applied using the dangerous technique of mercury gilding: a mixture of gold powder and mercury was mixed into a paste and painted onto the surface before the mercury was burned off. Ordinances issued by the Goldsmiths' Company of London in the late 14th century forbade the gilding of base metal objects that might be passed off as gold but this was often ignored.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Font Cup |

| Materials and techniques | Bronze, cast and engraved, formerly gilt |

| Brief description | Circular standing cup of bronze on wide stepped conical base |

| Physical description | Circular standing cup of copper alloy, cast, standing on a wide stepped conical base, the bowl shallow with steep sides, the outside of the bowl engraved '+NOLI. INEBRIari.VINO.QUO.EST. LVxv RIA. x'. There are remain of gilding on the inside of the base as well as three old collector's labels: "Col Lyons"' "640", "L". |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | +NOLI.INEBRIARI.VINO.QUO.EST. LVXVRIA (This is a quotation from the Bible, Ephesians chapter V,verse 18)

|

| Credit line | Lt. Col. G. B. Croft-Lyons Bequest |

| Object history | The cup came to the Museum as part of the Croft Lyons Bequest in 1926. Colonel Croft Lyons was an early member of the Pewter Society (founded in 1918) and an avid collector of ceramics, furniture, textiles and base metalwork. His bequest added over 700 pieces of metalwork to the collection including large collections of brass and pewter. Historical significance: The Latin inscription,though derived from the Bible, may be ironically intended |

| Historical context | Throughout the Middle ages and into the Renaissance, prestige lay in the ownership and display of gold and silver drinking vessels.Large cups like this were used on formal occasions for ceremonial toasts and thanksgiving, and were displayed on buffets when not in use. Cups might be treasured as heirlooms, which accounts for many that survive. At banquets, cups marked the status of the chief guest and the drinking of wine was generally a ritualised ceremony. This plain copper alloy cup, orginally gilded, imitates silver-gilt versions and is, in its form, a standing bowl, which would originally have had a cover. This shape of cup seems to appear around 1500, and was known as a 'flatpece'. Its shallow wide bowl and robust, simple design has led such cups to be referred in modern literature as 'font cups'. By the mid-16th century the shape had evolved into the shallow bowls popular in much of northern Europe. A number of font cups were later used in English churches as communion cups and patens. Much of the gilding on the cup has been rubbed away. Traces survive under the trumpet shaped foot. The gilding was applied using the dangerous technique of mercury gilding: a mixture of gold powder and mercury was mixed into a paste and painted onto the surface before the mercury was burned off. Ordinances issued by the Goldsmiths' Company of London in the late 14th century forbade the gilding of base metal objects like this, that might then be passed off as gold, but this was often ignored. Today this cup is exceptionally rare, since most other copper examples have been melted down. |

| Production | Compares in style to 'The Campion Cup', hallmarked 1500-01, V&A, M.249-1924 |

| Summary | This plain copper alloy cup, orginally gilded, imitates silver-gilt versions and is, in its form, a standing bowl, which would originally have had a cover. Throughout the Middle ages and into the Renaissance, prestige lay in the ownership and display of gold and silver drinking vessels.Large cups like this were used on formal occasions for ceremonial toasts and thanksgiving, and were displayed on buffets when not in use. Cups might be treasured as heirlooms, which accounts for many that survive. At banquets, cups marked the status of the chief guest and the drinking of wine was generally a ritualised ceremony. This cup, in the form of a standing bowl, would originally have had a cover.This shape of cup seems to appear around 1500, and was known as a 'flatpece'. Its shallow wide bowl and robust, simple design has led such cups to be referred to in modern literature as 'font cups'. By the mid-16th century the shape had evolved into the shallow bowls popular in much of northern Europe. A number of font cups were later used in English churches as communion cups and patens. This cup is of gilt copper alloy, although much of the gilding has been rubbed away. Traces survive under the trumpet shaped foot. The gilding was applied using the dangerous technique of mercury gilding: a mixture of gold powder and mercury was mixed into a paste and painted onto the surface before the mercury was burned off. Ordinances issued by the Goldsmiths' Company of London in the late 14th century forbade the gilding of base metal objects that might be passed off as gold but this was often ignored. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.880-1926 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | October 31, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest