Ring

1500-1600 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

A belief in the magical or curative properties of gemstones, minerals and other natural materials has long existed. The brown stone set into this ring was known as a toadstone. Toadstones were especially popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods. They were most often set in rings - the natural shape of the toadstone fitted a ring bezel well, and the toadstone could be worn daily and touched or monitored for any changes.

The round, brown toadstone, also known as 'crapaudine' or 'crappot', was believed to be effective against kidney disease and was a sure talisman of earthly happiness, according to Johannes de Cuba, writing in his Hortus Sanitatis (Garden of Health) in 1498. Wearers also believed that it would give off heat if exposed to poison. This was described by Fenton in 1569 "Being used in rings they give forewarning of venom". In 1627, Lupton claimed that ‘A Tode stone (called Crapaudina) touching any part be venomed, hurte or stung with Ratte, Spider, Waspe or any other venomous Beasts, ceases the paine or swelling thereof’. It was also said to protect pregnant women from fairies and demons and to prevent their child being exchanged for a changeling.

Toadstones were highly valued and often appeared in contemporary literature – according to Shakespeare’s ‘As you like it’:

‘Sweet are the uses of adversity;

Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.’

They were included in the stock of many jewellers. An unmounted toadstone was found as part of the Cheapside Hoard (now in the Museum of London), the stock of a 17th century jeweller which was found in the cellar of a London house in the early 20th century.

Despite the name and former beliefs, toadstones are the fossilised teeth of a fish of the Jurassic and Cretaceous period called 'Lepidotes'. Lepidotes had a mouth with a wide palate set with rows of rounded, peg-like teeth which it used to crush the shells of molluscs.

This ring forms part of a collection of over 600 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-81). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899.

Edmund Waterton used the fortune which was made by his family’s involvement in the British Guiana sugar plantations to put his collection together. His grandfather owned a plantation known as Walton Hall and his father, Charles Waterton, went to Guiana as a young man to help run La Jalousie and Fellowship, plantations which belonged to his uncles. When slavery was abolished in the British territories, Charles Waterton claimed £16283 6s 7d in government compensation and was recorded as having 300 slaves on the Walton Hall estate.

The round, brown toadstone, also known as 'crapaudine' or 'crappot', was believed to be effective against kidney disease and was a sure talisman of earthly happiness, according to Johannes de Cuba, writing in his Hortus Sanitatis (Garden of Health) in 1498. Wearers also believed that it would give off heat if exposed to poison. This was described by Fenton in 1569 "Being used in rings they give forewarning of venom". In 1627, Lupton claimed that ‘A Tode stone (called Crapaudina) touching any part be venomed, hurte or stung with Ratte, Spider, Waspe or any other venomous Beasts, ceases the paine or swelling thereof’. It was also said to protect pregnant women from fairies and demons and to prevent their child being exchanged for a changeling.

Toadstones were highly valued and often appeared in contemporary literature – according to Shakespeare’s ‘As you like it’:

‘Sweet are the uses of adversity;

Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.’

They were included in the stock of many jewellers. An unmounted toadstone was found as part of the Cheapside Hoard (now in the Museum of London), the stock of a 17th century jeweller which was found in the cellar of a London house in the early 20th century.

Despite the name and former beliefs, toadstones are the fossilised teeth of a fish of the Jurassic and Cretaceous period called 'Lepidotes'. Lepidotes had a mouth with a wide palate set with rows of rounded, peg-like teeth which it used to crush the shells of molluscs.

This ring forms part of a collection of over 600 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-81). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899.

Edmund Waterton used the fortune which was made by his family’s involvement in the British Guiana sugar plantations to put his collection together. His grandfather owned a plantation known as Walton Hall and his father, Charles Waterton, went to Guiana as a young man to help run La Jalousie and Fellowship, plantations which belonged to his uncles. When slavery was abolished in the British territories, Charles Waterton claimed £16283 6s 7d in government compensation and was recorded as having 300 slaves on the Walton Hall estate.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Iron; fossilized tooth |

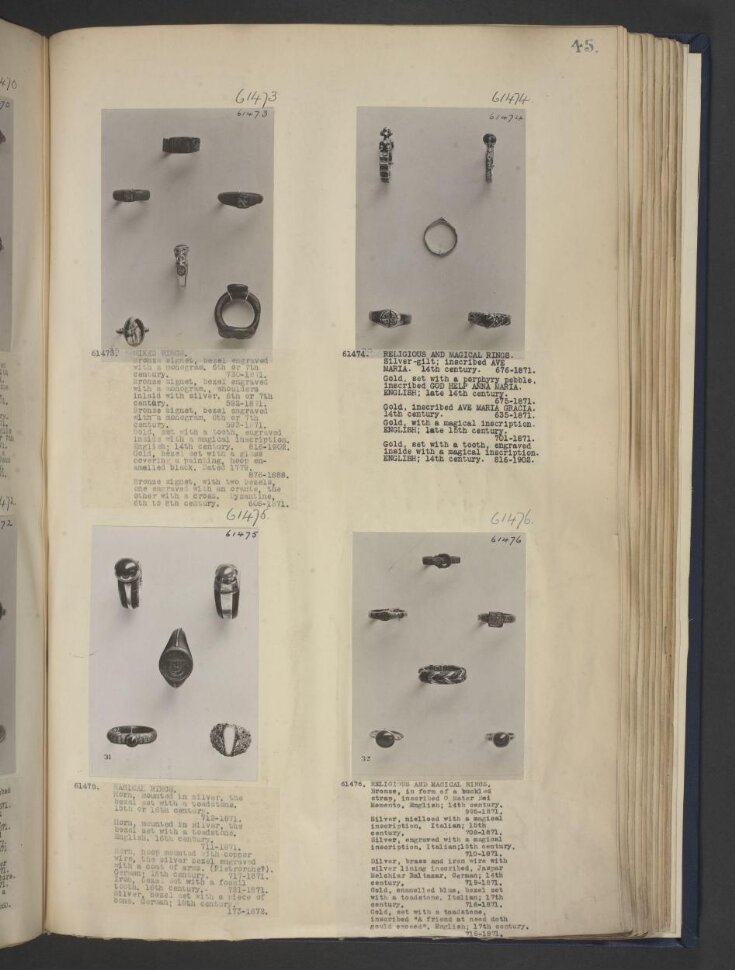

| Brief description | Iron ring with a small circular bezel set with a conical piece of fossilized tooth.Western Europe, 1500-1600 |

| Physical description | Iron ring, the hoop in rectangular segments and decorated with scale ornament. The small circular bezel set with a conical piece of fossilized tooth. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | ex Waterton Collection |

| Summary | A belief in the magical or curative properties of gemstones, minerals and other natural materials has long existed. The brown stone set into this ring was known as a toadstone. Toadstones were especially popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods. They were most often set in rings - the natural shape of the toadstone fitted a ring bezel well, and the toadstone could be worn daily and touched or monitored for any changes. The round, brown toadstone, also known as 'crapaudine' or 'crappot', was believed to be effective against kidney disease and was a sure talisman of earthly happiness, according to Johannes de Cuba, writing in his Hortus Sanitatis (Garden of Health) in 1498. Wearers also believed that it would give off heat if exposed to poison. This was described by Fenton in 1569 "Being used in rings they give forewarning of venom". In 1627, Lupton claimed that ‘A Tode stone (called Crapaudina) touching any part be venomed, hurte or stung with Ratte, Spider, Waspe or any other venomous Beasts, ceases the paine or swelling thereof’. It was also said to protect pregnant women from fairies and demons and to prevent their child being exchanged for a changeling. Toadstones were highly valued and often appeared in contemporary literature – according to Shakespeare’s ‘As you like it’: ‘Sweet are the uses of adversity; Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous, Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.’ They were included in the stock of many jewellers. An unmounted toadstone was found as part of the Cheapside Hoard (now in the Museum of London), the stock of a 17th century jeweller which was found in the cellar of a London house in the early 20th century. Despite the name and former beliefs, toadstones are the fossilised teeth of a fish of the Jurassic and Cretaceous period called 'Lepidotes'. Lepidotes had a mouth with a wide palate set with rows of rounded, peg-like teeth which it used to crush the shells of molluscs. This ring forms part of a collection of over 600 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-81). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899. Edmund Waterton used the fortune which was made by his family’s involvement in the British Guiana sugar plantations to put his collection together. His grandfather owned a plantation known as Walton Hall and his father, Charles Waterton, went to Guiana as a young man to help run La Jalousie and Fellowship, plantations which belonged to his uncles. When slavery was abolished in the British territories, Charles Waterton claimed £16283 6s 7d in government compensation and was recorded as having 300 slaves on the Walton Hall estate. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 721-1871 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 17, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest