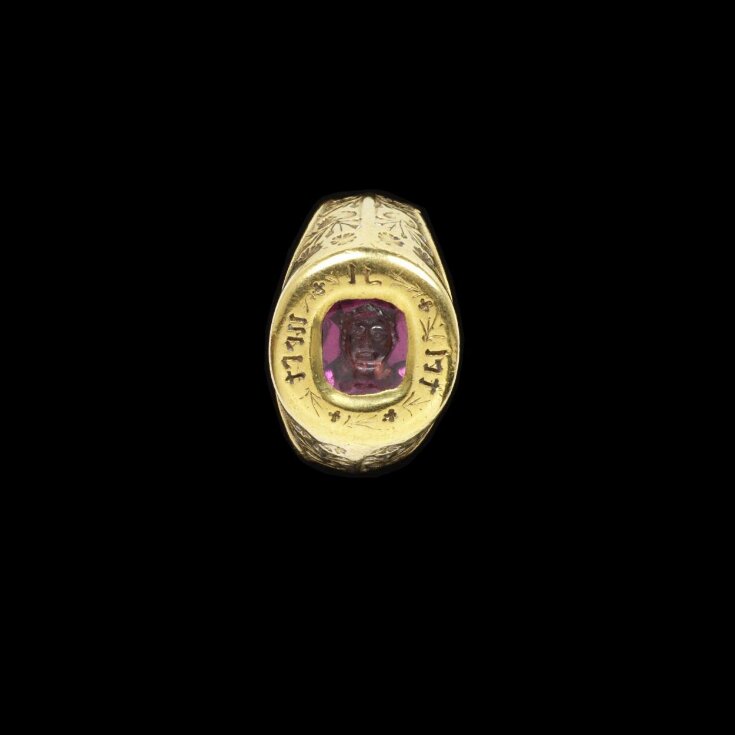

Signet Ring

1400-1500 (made), late 14th century (intaglio)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Rings are the most commonly surviving medieval jewels. They were worn by both sexes, across all levels of society. Some portraits show wearers with multiple rings across all their fingers. Although rings were worn for decoration, they also had important practical functions. Signet rings such as this one were pressed into sealing wax to create a unique, legally recognised signature. It has been suggested that this finely carved spinel may be the stone listed in the 1379 inventory of King Charles V of France, described as The signet of the King which is the head of a king without beard; and is (made) of a fine oriental ruby; this is that which the King seals the letters which he has written with his (own) hand.

The head on the ring resembles that of Charles V seen on coins, but the style of the ring itself is more typical of the 15th century. It is possible that although the spinel was carved in the mid 14th century, it was reused in a slightly later ring.

Gemstones were highly valued in the medieval world, sapphires, rubies, garnets, amethysts and rock crystal being the most commonly used. Diamonds were highly valued but much less common. They were valued, as now, for their colour and lustre but also for their perceived amuletic or talismanic powers. Books known as 'lapidaries' listed the powers attributed to each stone. Rubies and spinels (known as balas rubies) were said to promote health, reconcile enemies and combat excessive lust.

The head on the ring resembles that of Charles V seen on coins, but the style of the ring itself is more typical of the 15th century. It is possible that although the spinel was carved in the mid 14th century, it was reused in a slightly later ring.

Gemstones were highly valued in the medieval world, sapphires, rubies, garnets, amethysts and rock crystal being the most commonly used. Diamonds were highly valued but much less common. They were valued, as now, for their colour and lustre but also for their perceived amuletic or talismanic powers. Books known as 'lapidaries' listed the powers attributed to each stone. Rubies and spinels (known as balas rubies) were said to promote health, reconcile enemies and combat excessive lust.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Engraved gold set with a purple spinel intaglio with traces of enamel |

| Brief description | Gold signet ring with an oval bezel set with a purple spinel intaglio of a crowned head and engraved in black letter tel il nest ('There is none like him'). The intaglio France, late 1350-1400, the setting England, 1400-1500. |

| Physical description | Gold signet ring with an oval bezel set with a purple spinel intaglio of a crowned head and engraved in black letter tel il nest The shoulders engraved with sprigs, with traces of enamel |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | inscribed tel il nest (in black letter)

|

| Credit line | Salting Bequest |

| Object history | ex Arundel and Marlborough Collections. Listed on the Beazley Archive website, (see references). George Salting was born in Australia on 15 August 1835, the elder son of Severin Kanute Salting (1805-1865), a wealthy businessman and landowner, and Louisa Augusta, née Fiellerup. Following an education at Eton College, 1848-53, and the University of Sydney, from where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1857, Salting settled in London. In 1858-59 he toured the continent, visiting galleries, churches and architectural monuments. After the death of his father on 14 September 1865, he inherited a fortune estimated at £30,000 per annum and devoted himself thereafter to the study and collecting of works of art including lacquer and Oriental porcelain. Such was the extent of the accumulations that filled his rooms above the Thatched House Club at 86 St James's Street, London, that in 1874 Salting started to deposit items on loan in the South Kensington Museum. The Frederic Spitzer sale of Medieval and Renaissance objects d’art in 1893 resulted in a diversification of Salting’s collecting interests: Italian majolica, bronzes and reliefs, Persian, Damascas and Turkish ware, Limoges enamels, illuminated manuscripts, carved woodwork and tapestries, and Japanese lacquer and European steel and iron. He died on 12 December 1909 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, London. Salting bequeathed works to the National Gallery, British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum. The Trustees of the National Gallery received those works which were already on loan and were also allowed to select those from Salting's Collection which they would like to receive. In total this amounted to 192 works. The pictures were hung in the Gallery in 1911. There were no special conditions attached to the bequest. Salting bequeathed his prints and drawings to the British Museum and a substantial number of objects to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The bequest to the V&A was conditional that the objects would not be distributed over various sections but all kept together. Including three works presented during his lifetime, there are currently 164 works in the National Gallery Collection which have been donated by Salting. In addition, thirty-one of the works bequeathed by Salting are now held by the Tate Gallery. |

| Production | Intaglio probably 1350-1400 |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Rings are the most commonly surviving medieval jewels. They were worn by both sexes, across all levels of society. Some portraits show wearers with multiple rings across all their fingers. Although rings were worn for decoration, they also had important practical functions. Signet rings such as this one were pressed into sealing wax to create a unique, legally recognised signature. It has been suggested that this finely carved spinel may be the stone listed in the 1379 inventory of King Charles V of France, described as The signet of the King which is the head of a king without beard; and is (made) of a fine oriental ruby; this is that which the King seals the letters which he has written with his (own) hand. The head on the ring resembles that of Charles V seen on coins, but the style of the ring itself is more typical of the 15th century. It is possible that although the spinel was carved in the mid 14th century, it was reused in a slightly later ring. Gemstones were highly valued in the medieval world, sapphires, rubies, garnets, amethysts and rock crystal being the most commonly used. Diamonds were highly valued but much less common. They were valued, as now, for their colour and lustre but also for their perceived amuletic or talismanic powers. Books known as 'lapidaries' listed the powers attributed to each stone. Rubies and spinels (known as balas rubies) were said to promote health, reconcile enemies and combat excessive lust. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.554-1910 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 15, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest