Arrival of a Portuguese ship

Screen

1600-1630 (made)

1600-1630 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

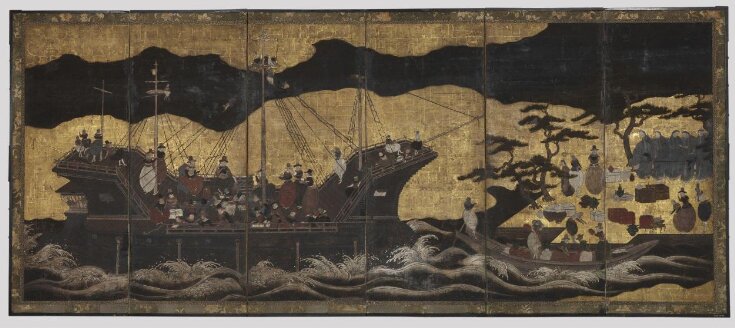

This Japanese screen, painted in the early seventeenth century, depicts the arrival of a Portuguese ship in Nagasaki. It reveals the Japanese fascination with the strange physical features and curious costumes of the nanbanjin, or ‘southern barbarians’, as the Portuguese were termed. Dating from the mid 1590s to the late 1630s, there are almost seventy surviving examples of this type of screen, an indication of the popularity of the theme.

The screen was probably painted for a wealthy merchant. Such a commission would have been motivated by a genuine interest in the ‘exotic’ foreigners, a strong sense of the business opportunities offered by the encounter and a desire for knowledge of the new, wider, world that the Portuguese had brought so unexpectedly to Japan’s shores. While taking Europe and trade with Europeans as its theme, the subject depicted on the screen also relates to traditional Japanese iconography. The Portuguese ship represents a treasure ship (takara-bune) bringing wealth and happiness from over the seas. The Europeans themselves were viewed by the Japanese as other-worldly creatures and the bearers of good fortune. Indeed, the first Portuguese seemed to have arrived as a gift from the gods, brought as they were by a kamikaze or ‘divine wind’.

The screen was probably painted for a wealthy merchant. Such a commission would have been motivated by a genuine interest in the ‘exotic’ foreigners, a strong sense of the business opportunities offered by the encounter and a desire for knowledge of the new, wider, world that the Portuguese had brought so unexpectedly to Japan’s shores. While taking Europe and trade with Europeans as its theme, the subject depicted on the screen also relates to traditional Japanese iconography. The Portuguese ship represents a treasure ship (takara-bune) bringing wealth and happiness from over the seas. The Europeans themselves were viewed by the Japanese as other-worldly creatures and the bearers of good fortune. Indeed, the first Portuguese seemed to have arrived as a gift from the gods, brought as they were by a kamikaze or ‘divine wind’.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Arrival of a Portuguese ship (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Ink, colours and gold leaf on paper |

| Brief description | Six fold screen, Arrival of a Portugese Ship, ink colours and gold leaf on paper, Japan, 1600-1630 |

| Physical description | Six-fold screen depicting the arrival of a Portuguese ship in a Japanese port. Scenes portrayed on Japanese screens are usually read from right to left, but in keeping with its ‘exotic’ subject the scene on this screen moves from left to right. On the left a ship is anchored, its dark form silhouetted against a large expanse of gold. On board are the captain-major, seated on a grand chair, and a companion being served drinks by a dark-skinned, probably South Asian, attendant. The pair are surrounded by merchants while overhead small figures dismantle the rigging with acrobatic flair. To the right a boat ferries passengers and their cargoes to shore. Here the various goods, probably from China, are unloaded, the scene being witnessed by a group of Jesuit priests standing beneath pine trees. The Japanese were fascinated by the curious appearance of the Portuguese and here the artist has emphasised, in an almost comic manner, the long noses and balloon-like trousers of the foreigners. The screen is mounted with a double textile border, a thin brocade strip of blue and gold and a wider strip of green-gold silk embroidered with flowers in orange and cream-yellow (although the colours have greatly faded). This fabric may, like the screen, be early seventeenth century although it is difficult to be sure. The back of the screen is of Japanese paper made to look like leather, an 'exotic' European material much admired in Japan since its first introduction by the Dutch in the seventeenth century. The paper dates to the late nineteenth century although the pattern, which includes European style putti, relates to the Sokenkisho pattern book which was first published in 1781 and came out in numerous later editions. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | Purchased from Sir John Pope Hennessy, accessioned in 1892. This acquisition information reflects that found in the Asia Department registers, as part of a 2022 provenance research project. This screen was probably painted in Kyoto by a Kano artist. This family-based school dominated Japanese painting from the 16th to19th centuries, and the majority of painters received their initial training under a Kano master. The school is most famous for monumental landscape, figure and bird-and-flower compositions executed for the Shogun and high ranking samurai, but in the Edo period (163-1868) some Kano artists painted genre scenes for the merchant classes. One of these so called machi-kano or 'urban Kano' artists was probably responsible for this screen which would have been painted for a wealthy merchant. From 1883, the screen was on loan to the V&A from Sir John Pope Hennessy (1834-1891), British diplomat and 8th Govenor of Hong Kong. In 1892 the Museum purchased the screen from Hennessy's widow. |

| Historical context | The first Europeans to arrive in Japan did so by accident rather than design. The vessel in which they were travelling was blown off course by a typhoon, shipwrecking the Portuguese sailors on the island of Tanegashima off the tip of south-west Japan in the early 1540s. Eager to trade with Japan, the Portuguese soon established a more formal traffic via Nagasaki in south-west Japan, and in 1549 the Jesuit priest Francis Xavier arrived in the country to found the first Christian mission. For the Japanese, any initial feelings of alarm caused by the actual appearance of the nanbanjin, or ‘southern barbarians’, as the Portuguese were termed, were soon overshadowed by the exotic appeal of these curious visitors. The fascination aroused by the strange physical features and outlandish costumes of the Europeans is revealed in many aspects of late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Japanese visual culture, most dramatically in screens such as this that depict the arrival of a Portuguese vessel in a Japanese port. This is one of nearly seventy surviving examples of single or paired screens which depict the arrival of the Portuguese. With the exception of those depicting scenes in and around Kyoto (a genre known as ‘rakuchu rakugai’) this is largest group of Japanese screens on one subject, an indication of the enormous popularity of the theme. The screens can be categorised into three main types. The most numerous are those in which the left hand screen shows the arrival of the ship and the right hand screen the procession of a captain-major on shore. In the second group these two scenes are compressed in the right hand screen and on the left screen the ship’s departure from an imagined foreign port, probably meant to represent Goa or Macao, is depicted. In the third group the left hand screen shows horse racing, or other activities, in another foreign country, possibly China. The screen illustrated here is likely to be the left screen of a pair of one of the first group. The production of such screens was part of the fashion for nanban, or ‘southern barbarian’, culture that was inspired, at least in part, by the return of Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606) and four young Japanese who had travelled to Europe. In March 1591 Valignano led the envoys, accompanied by sumptuously dressed Portuguese officials, in a lavish procession through the streets of Kyoto (known at the time as Miyako) to the court of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1568-1595) the de facto ruler of Japan. Another important event in the development of the nanban craze was the gathering of more than thirty daimyo (feudal lords) and over a hundred thousand soldiers at the newly-built Nagoya Castle in Hizen, Hideyoshi’s headquarters for the Korean campaign of 1592-3. The castle’s proximity to Nagasaki meant that many samurai were able to experience the ‘southern barbarians’ first hand. The artist Kano Mitsunobu (1561/5-1608) was employed in producing fusuma (painted doors) for the castle and, as one of the earliest nanban screens is attributed to him, it is possible that he also took the opportunity to travel to Nagasaki and make sketches on which his screen was based. Some scholars have cast doubt on this theory, however, for there is no evidence that he, or any other Kano school artist, ever visited Nagasaki, nor is there anything in the screens to suggest that the port depicted is actually Nagasaki. The images on these screens are not rooted in any specific reality, but are a reflection of the tastes and interests of those for whom they were painted. The emphasis is on the exotic appearance of the foreigners and the exciting goods they bring on their ships. The majority of the the screens, which signal a new Japanese view of the world and an interest in what it has to offer, were painted by lesser artists of the Kano school working in Kyoto. Research into the provenance of the screens has revealed that most of them were commissioned by wealthy merchants and shipping agents in port towns on the Japan and Inland Sea coasts. While taking Europe and Europeans as their ostensible theme, the subjects depicted on the screens relate to traditional Japanese iconography. The nanban ship represents a treasure ship (takara-bune) bringing wealth and happiness from over the seas, an auspicious motif that would have been particularly treasured by a merchant engaged in maritime transportation. The Portuguese themselves were viewed as almost supernatural beings and the bearers of good fortune. Screens such as this were painted from the mid 1590s until the late 1630s when the Portuguese were expelled from Japan and Christianity prohibited. |

| Production | Probably painted in Kyoto by an artist of the Kano school |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This Japanese screen, painted in the early seventeenth century, depicts the arrival of a Portuguese ship in Nagasaki. It reveals the Japanese fascination with the strange physical features and curious costumes of the nanbanjin, or ‘southern barbarians’, as the Portuguese were termed. Dating from the mid 1590s to the late 1630s, there are almost seventy surviving examples of this type of screen, an indication of the popularity of the theme. The screen was probably painted for a wealthy merchant. Such a commission would have been motivated by a genuine interest in the ‘exotic’ foreigners, a strong sense of the business opportunities offered by the encounter and a desire for knowledge of the new, wider, world that the Portuguese had brought so unexpectedly to Japan’s shores. While taking Europe and trade with Europeans as its theme, the subject depicted on the screen also relates to traditional Japanese iconography. The Portuguese ship represents a treasure ship (takara-bune) bringing wealth and happiness from over the seas. The Europeans themselves were viewed by the Japanese as other-worldly creatures and the bearers of good fortune. Indeed, the first Portuguese seemed to have arrived as a gift from the gods, brought as they were by a kamikaze or ‘divine wind’. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 803-1892 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 15, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest