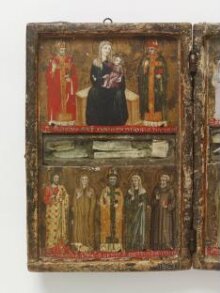

The Virgin and Child with Saints Blasius and Nicholas; Saints Bartholomew, Mary Magdalen, Urban, Agatha and Anthony

Tempera Painting

ca. 1300-1350 (painted)

ca. 1300-1350 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This is a small reliquary diptych which opens and closes like a book. Its exterior shows traces of imitation marbling. Its interior comprises painted panels divided by a hollowed-out area in the middle which still holds relics, wrapped in paper and labelled. At the top left is depicted the Virgin and Child enthroned, flanked by St. Blasius and St. Nicholas. Below appear St. Bartholomew, St. Mary Magdalene, St. Urban, St. Agatha and St. Anthony. At the top right the Crucifixion is represented, with a male donor wearing a monastic habit, flanked by the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, St. Scholastica and St. Agnese. Below appear St. Emilian, St. Costanza and an unidentified female saint. Their names are inscribed in Latin beneath the figures.

Relics of saints played a major role in medieval religious life. Although they were venerated, relics not supposed to be worshipped, and acted as an aid to secure the intercession of saints. They were often kept in reliquaries, accompanied by images of their saints. In this example, only St. Bartholomew, who holds his customary knife, is readily identifiable by an accompanying attribute. The black robe of the donor figure suggests that he was a Benedictine monk. The generic character of the images of bishops and holy women may indicate that the diptych was made to accommodate a collection of relics which was still being added to. Its small scale suggests that it was intended to be portable.

It is unknown who made this reliquary, but it was most probably produced in the vicinity of Spoleto in Umbria in the 1320s, perhaps in a monastic workshop. Its style closely resembles that of two small panels from the church of Sant' Alo' in Spoleto. Although this diptych is made of modest materials - gilded and painted wood - rather than the precious metals and expensive enamels reserved for grander reliquaries, it has been carefully painted, with exquisitely-delineated draperies, by an artist of considerable skill.

Relics of saints played a major role in medieval religious life. Although they were venerated, relics not supposed to be worshipped, and acted as an aid to secure the intercession of saints. They were often kept in reliquaries, accompanied by images of their saints. In this example, only St. Bartholomew, who holds his customary knife, is readily identifiable by an accompanying attribute. The black robe of the donor figure suggests that he was a Benedictine monk. The generic character of the images of bishops and holy women may indicate that the diptych was made to accommodate a collection of relics which was still being added to. Its small scale suggests that it was intended to be portable.

It is unknown who made this reliquary, but it was most probably produced in the vicinity of Spoleto in Umbria in the 1320s, perhaps in a monastic workshop. Its style closely resembles that of two small panels from the church of Sant' Alo' in Spoleto. Although this diptych is made of modest materials - gilded and painted wood - rather than the precious metals and expensive enamels reserved for grander reliquaries, it has been carefully painted, with exquisitely-delineated draperies, by an artist of considerable skill.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Virgin and Child with Saints Blasius and Nicholas; Saints Bartholomew, Mary Magdalen, Urban, Agatha and Anthony (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Tempera on panel |

| Brief description | Left panel of reliquary diptych, showing the Virgin and Child with saints, possibly painted by an artist of the Umbrian School, ca. 1300-1350 |

| Physical description | This is the left panel of the reliquary diptych (see also the right panel, 20-1869). The diptych would have been opened and closed like a book, and its back shows traces of imitation marble painting. Both sides have painted panels divided by a hollowed-out area in the middle which still holds relics wrapped in paper and labeled. The top of the left side shows the Virgin and Child enthroned flanked by St Blasius on her right and St Nicholas on her left. The lower panel shows (from left to right) St Bartholomew, St Mary Magdalene, St Urban, St Agatha and St Anthony. The Latin names of the saints are inscribed in white on a red border at the bottom of each panel. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | (beneath top image) S.BLASIUS.MAT[ER] DEI ORA P[RO] NOB[IS].S.NICOLAS

(beneath bottom image) S.BARTHOLOMEUS.S.M[ARI]A MA[G]D[LEN]A. S.URBAN. S.AGATHA. S.ANTONI[US] (Letters in square brackets are indicated in the original inscription by abbreviation marks or floating letters.)

|

| Object history | The diptych was formerly owned by Serafino Tordelli (1787-1864), a collector from Spoleto. Bruno Toscano identified it as the diptych described in the inventory of Tordelli’s collection compiled by his heirs after his death for the sale of the collection (Toscano, 1966, p.20, p.31 n.42). A note written in 1940 on the back of a drawing of Tordelli’s main room described it as “…drawn by Giovanni Montiroli (Tordelli’s nephew) on October 13, 1868. The collection was sold to a certain Baslini from Milan for 60,000 lire.” (Fratellini, 134). Giuseppe Baslini (1817-1877) was a well-known antiquarian and dealer in Milan (Fratellini, 134). Toscano suggested the V&A diptych may have arrived in London through the English connections of Tordelli’s nephew Giovanni Montiroli, who worked in England as architect to the Dukes of Northumberland and Marlborough. (Toscano, p.21). The approval of the purchase of the reliquary for £4 from Baslini was 17 July 1868, though the exact date of purchase is not clear. Other objects from the Tordelli collection also figure on the list, including two mortars, a cassone panel and a medal of Pope Alexander VII. (Museum archives). Kauffman’s assertion that the diptych was purchased in December of 1868 is therefore incorrect, as that is the date it was received into the museum from the stores (Kauffman, museum file notes). Seen under a microscope, the diptych reveals very carefully painted faces, a gilded background and exquisite drapery. The gilding has been overlaid with a tonal varnish which has darkened over time. The original appearance would have been much brighter. Azurite appears to have been used for the blues, and vermillion and red lacquer glaze for the reds. The glass in the center appears to have been added at a later date. It appears younger than the rest of the diptych and is not flush with the edges. Historical significance: Reliquary diptychs dating from the early 1300s that retain their original appearance are unusual. The V&A diptych is in good condition, though the relics seem to have shifted in transit. From left to right, they appear as follows: “S. Blas[i]s,” “[…] ù panu madalena,” an unidentified piece of gold cloth twisted into a knot, “de ecclia b[eat]e virgínis in nazaretj ubi […]x pir […]nij,” “de panone agathe q[uam] posit fuit ne igne,” “da S. Nicolo,” and the last has been turned over and its inscription cannot be seen. On the right hand side, some of the relics have been removed. The remaining relics have shifted and appear from left to right as follows: a scrap of paper, part of what appears to be a bone fragment, a small paper on its side that has been opened (with the relic removed) with the writing facing the lower section and therefore not legible, a larger piece of paper with an illegible inscription, possibly referring to the cross, a piece of bone fragment and a small bit of paper. As noted above, reliquaries typically depict the saints whose relics they contain, who are identifiable by their attributes or inscriptions. On the V&A diptych, none of the female saints have significant attributes except for the Virgin Mary and the Magdalene. The three women who carry stylized lilies and a palm have been labeled as Scholastica and Agnese on the upper right flanking the Crucifixion, and Agostantia on the lower right center. It is not clear if the last is meant to indicate Costanza, though it seems the most likely possibility. The female saint on the rightmost side does not have any inscription. The male saints are also rather generic, except for Bartholomew, who holds a knife in his right hand. None of the bishops display any identifying attributes other than the bishop’s crook and the mitre. The bishop saints are identified as Blasius, Nicholas, Urban and Emiliano. The bearded saint wearing a monastic brown habit on the lower left seems to be identifiable as St Anthony Abbot based on the inscription, yet he is more commonly shown in a black robe. The configuration of saints does not indicate an easily identifiable location for the diptych’s original location. Relics of the early Christian martyrs were highly prized, and this could certainly explain the presence of the early Christian martyrs (Bartholomew, Agatha, Agnes) on the V&A diptych. St Biagio’s relics have been said to exist in such abundance that their authenticity must sometimes be questioned (Biblioteca Sanctorum, iii, p.158). St Anthony Abbot, St Scholastica and the donor under the crucifix provide a monastic context. The donor’s black robe could indicate that he was Benedictine. This would also explain the presence of St Scholastica, who was St Benedict’s sister, but does not explain the absence of St Benedict himself. The three bishop saints (Blasius, Nicholas, Urban) were popular saints, though the fourth, Emilian, was less well-known. Umbria had many Benedictine monasteries, and its Spoletan provenance could indicate that the reliquary came from a near-by monastery. A likely theory for the presence of disparate saints with no attributes is that the Benedictine monk who owned or commissioned the reliquary had the relics of Sts Bartholomew and Mary Magdalene, and was planning to collect more. Since he may not have known which relics he would find, he had the artist paint the known saints and requested that generic figures of holy men and women be added to fill up the remaining space on the diptych. This could also explain why the last female saint on the lower right hand side does not have an identifying inscription. The format of the reliquary diptych as a book to be read from left to right would also reflect the order of inscriptions. It is highly unusual to find saints with no attributes – especially in a society with low literacy. This presupposes a literate owner – as the inscriptions naming the saints are the only way they are identified. The writing on the relic paper is (as was typical) in Latin and describes their contents in detail. If the practice was to add inscriptions and figures as one collected relics, this also assumes that the local workshop maintained contacts with the owner. Given the history of the monastic orders and book illumination, it is worth considering that this and other reliquaries, may have been produced in a monastery workshop. When the diptych was purchased it was thought to be Sienese. It has since been variously attributed though with most scholars agreeing on an Umbrian provenance. Its presence in the Tordelli collection of Spoleto could also support this theory; though it must be noted that Tordelli had about 1000 objects in his collection with a wide range of origins. (Toscano, 1966). Van Marle believed the work came from the school of Meo da Siena – a Sienese artist who moved to Perugia yet was influenced by Riminese artists. He felt that the presence of St Emilian meant that it must have come from Perugia (Van Marle, v, p.36). Volbach assigned it to a group of works produced in Umbria in the 1320s. He believed it came from the area of Trevi or Montefalco and compared it to the work of the Santa Chiara master at Montefalco and a reliquary diptych in the Staatliche Museum in Berlin (Volbach, 177). Santangelo attributed it directly to the master of the Santa Chiara frescoes at Montefalco, and also compared a reliquary diptych in the Palazzo Venezia Museum in Rome (Santangelo, p.5). Boskovits believed the V&A diptych came from an early 14th century Spoletan circle which included the Master of the Poldi-Pezzoli diptych. This school was influenced by recent developments caused by the immigration of Roman artists to Assisi (Boskovits, 117). Kauffmann assigned the V&A diptych to the more general “Umbrian school.” He did not believe that it was by the same artist who painted the frescoes in the Church of Santa Chiara in Montefalco. (Kauffmann, no. 346). Todini noted that prior to 1864 the V&A diptych was in the Tordelli collection in Spoleto, though he did not cite Toscano. He attributed it to the “First Master of the Beata Chiara of Montefalco,” an anonymous painter who worked in Spoleto and Montefalco during the first half of the 14th century. He believed this master to be a follower of the “Master of Cesi,” a Roman artist active in Spoleto and Assisi. According to Todini, his works included (among others) the Pala di Foligno in Santa Maria Giaccobe, frescoes in the church of Santa Chiara in Montefalco and a diptych in the Palazzo Venezia museum in Rome. (Todini, 105). The V&A diptych has some similarities with the reliquary diptych in the Palazzo Venezia, especially in terms of the written inscriptions. However, the punching in the haloes is quite different. The V&A diptych has very simple circular punches inside a painted black line which marks the edge of the halo. The halos on the Palazzo Venezia diptych include simple circle punches to mark the edge of the haloes and small stars inside the haloes. Garrison noted a diptych from the oratory of S. Ansano in Fiesole, which include Sts. Paul, John the Baptist, Francis, Agnes, Catherine, Clara, Lucy, a kneeling Franciscan and a Crucifixion, though he did not reproduce it (Garrison, no. 242). As described by Garrison, this diptych has a more symmetrical layout than the V&A diptych with four saints on the upper section and four on the lower. Donal Cooper (verbally) pointed out the presence of the Master of Sant' Alo' reliquary cross and small panels in the Spoleto museum. Surprisingly, no one (not even Toscano) has remarked in printi upon the similarities between the two small panels in Spoleto at Sant’Alò reproduced by Toscano and the V&A diptych. Boskovits made reference to this article and remarked on the similarities between the V&A diptych and a crucifixion at Sant’Alò but inexplicably ignored the small panels. After comparison of the Sant' Alo' panels and the V&A panels, it appears that they are all by the same hand or hands (as at least two different hands seem apparent). The panels at Sant’Alò are reliquaries with a crowd of saints shown below a tripartite section that holds the relics. It is not clear if they formed part of a diptych or if they were intended to be single panels. The tripartite section is covered in glass. There are inscriptions of saints’ names underneath the section holding the relics and below the saints’ feet. The inscriptions are very similar to the writing on the V&A diptych and on the Palazzo Venezia diptych. The composition and faces of the saints (in particular the bishop saint in the center) and their lack of specific attributes is also quite similar to that of the saints in the V&A reliquary. The Sant’Alò reliquaries include small stars in the halos which are very similar to the Palazzo Venezia diptych. The saints on the Palazzo Venezia diptych also appear to have only few attributes such as books and/or swords to identify them other than the inscriptions. They are in three quarters bust length, but on the whole are similar to the figures on the V&A diptych and the Sant’Alò panels. There are fourteen saints on one of the Sant’Alò panels and fourteen on the other. Some of the saints appear to be standing behind the others, as only their heads are visible. It is possible that the saints were added in what available space remained on the panel as their relics were acquired. The V&A reliquary also appears to have been created with the option to add saints and inscriptions, as there are five saints on the left side and only three on the other. When compared to the Sant’Alò panels, the V&A reliquary appears to represent the same type of object with fewer relics, based on the lower number of figures. The V&A reliquary also contains small dowel marks on the shelf upon which the glass rests, at positions which suggest it may have contained a tripartite frame as in the Sant’Alò panels. The similarities between the V&A reliquary diptych and the Sant’Alò diptych suggest that the two came from the same workshop, as yet unidentified but known as the Master of Sant' Alo' due to the provenance of the Spoleto museum's reliquary diptych. It quite possibly was a Benedictine monastery near Spoleto. |

| Historical context | A diptych is a picture consisting of two separate panels facing each other and usually joined at the centre by a hinge. Painted diptychs were particularly popular from the second half of the 13th century until the early 16th in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands. In some cases a single seated or standing figure occupied each panel, while others were decorated with a series of narrative scenes from the Life of Christ. They often functioned as small-scale devotional paintings intended for private rooms or small altars in side chapels or oratories and their sizes can vary from small examples for personal use to large works suitable for a chapel altar. Relics were an important part of religious life during the medieval period and into the early modern era. Catholic churches today still need a relic on or near the high altar. There are three levels within the hierarchy of relics – primary relics, which include parts of a saint’s body, secondary relics, which include something a saint owned, wore or touched, and tertiary relics, which include something that was touched to a saint’s body or tomb. The traffic in all types of relics (including stolen relics) was extremely popular during the Middle Ages. Though relics were venerated, they were not supposed to be worshipped. The purpose of relics was to aid in securing the intercession of the saints, which accounts in large part for their popularity. Relics were typically labeled in order to identify them and the saints to whom they pertained. This was further emphasized by an image of the saint or saints. Reliquaries were made in a variety of materials, from precious containers of rock crystal, silver, bronze, or gold to painted panels. Relics were often inserted into small cabinets within the panels which were then sealed off with wax, wood, or glass. |

| Production | The Virgin and Child with Saints Blasius and Nicholas; Saints Bartholomew, Mary Magdalen, Urban, Agatha and Anthony (reliquary diptych) |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This is a small reliquary diptych which opens and closes like a book. Its exterior shows traces of imitation marbling. Its interior comprises painted panels divided by a hollowed-out area in the middle which still holds relics, wrapped in paper and labelled. At the top left is depicted the Virgin and Child enthroned, flanked by St. Blasius and St. Nicholas. Below appear St. Bartholomew, St. Mary Magdalene, St. Urban, St. Agatha and St. Anthony. At the top right the Crucifixion is represented, with a male donor wearing a monastic habit, flanked by the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, St. Scholastica and St. Agnese. Below appear St. Emilian, St. Costanza and an unidentified female saint. Their names are inscribed in Latin beneath the figures. Relics of saints played a major role in medieval religious life. Although they were venerated, relics not supposed to be worshipped, and acted as an aid to secure the intercession of saints. They were often kept in reliquaries, accompanied by images of their saints. In this example, only St. Bartholomew, who holds his customary knife, is readily identifiable by an accompanying attribute. The black robe of the donor figure suggests that he was a Benedictine monk. The generic character of the images of bishops and holy women may indicate that the diptych was made to accommodate a collection of relics which was still being added to. Its small scale suggests that it was intended to be portable. It is unknown who made this reliquary, but it was most probably produced in the vicinity of Spoleto in Umbria in the 1320s, perhaps in a monastic workshop. Its style closely resembles that of two small panels from the church of Sant' Alo' in Spoleto. Although this diptych is made of modest materials - gilded and painted wood - rather than the precious metals and expensive enamels reserved for grander reliquaries, it has been carefully painted, with exquisitely-delineated draperies, by an artist of considerable skill. |

| Associated object | 20-1869 (Part) |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 19-1869 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 2, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest