Ring

ca. 1600 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased. 'Memento mori' (remember you must die) inscriptions and devices such as hourglasses, skulls, crossbones and skeletons became fashionable on many types of jewellery, reminding the wearer of the brevity of life and the necessity of preparing for life in the world to come.

The mark on the other side of the bezel is a merchant's mark, used by a trader to mark his goods and adopted as a signet by those not entitled to a coat of arms. The ring therefore combines a spiritual function with a practical commercial use. This ring was found in Guildford but merchant's marks were used across Northern Europe.

The mark on the other side of the bezel is a merchant's mark, used by a trader to mark his goods and adopted as a signet by those not entitled to a coat of arms. The ring therefore combines a spiritual function with a practical commercial use. This ring was found in Guildford but merchant's marks were used across Northern Europe.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Gold, engraved; enamel |

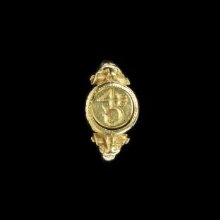

| Brief description | Gold ring, the revolving circular bezel enamelled with a skull on one side and on the other a merchant's mark. England, about 1600. |

| Physical description | Gold ring, the revolving circular bezel enamelled in white with a skull on one side, on the reverse with a merchant's mark, and on the edge with an inscription 'NOSSE TE IPSUM' (know yourself), with volutes on the shoulders. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | Ex Harman Oates Collection, found at Guildford. |

| Historical context | In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. References in wills such as that of William Shakespeare illuminate the way in which executors were asked to buy or have made rings for specific people for given amounts of money. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased. 'Memento mori' inscriptions and devices such as hourglasses, skulls, crossbones became fashionable in many types of jewellery and interior decoration, reminding the wearer of the briefness of life and the necessity of preparing for life in the world to come. 'Nosce te ipsum' was a popular motto on jewellery. In 1617, the will of Nicholas Fenay of Yorkshire describes a ring which was to be left to his son: 'having these letters NF for my name thereupon ingraved with this notable poesie about the same letters NOSCE TEIPSUM [sic know thyself] to the intent that my said son William Fenay in the often beholding and considering of that worthy poesye may be the better put in mynde of himselfe and of his estate knowing this that to know a man's selfe is the beginning of wisdom' (Scarisbrick, 1993, p. 49). The mark on the obverse of the revolving bezel is a merchant's mark, used to mark goods and as a signet for those not entitled to a coat of arms. Most merchants in the sixteenth and seventeenth century had marks, easily identifiable and formed with a few strokes of the brush. In England, most marks were like mastheads, designed around an inverted V, a double X or W, a reversed 4 or a combination of these elements. Many merchants rings also bear religious or talismanic inscriptions, combining a spiritual with a commercial function. See comparable ring in the British Museum with a revolving bezel showing a merchant's mark and an enamelled skull found at Banstead, Surrey (Museum number 1871,0302.5, Dalton 813) |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased. 'Memento mori' (remember you must die) inscriptions and devices such as hourglasses, skulls, crossbones and skeletons became fashionable on many types of jewellery, reminding the wearer of the brevity of life and the necessity of preparing for life in the world to come. The mark on the other side of the bezel is a merchant's mark, used by a trader to mark his goods and adopted as a signet by those not entitled to a coat of arms. The ring therefore combines a spiritual function with a practical commercial use. This ring was found in Guildford but merchant's marks were used across Northern Europe. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.18-1929 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 23, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest