The Parker Wine Fountain

Fountain

1719-1720 (hallmarked)

1719-1720 (hallmarked)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

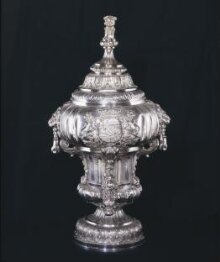

This wine fountain is from a set of silver for serving wine. The set also includes a cistern and cooler. It would have been arranged in tiers on a sideboard in the dining room, with the large and heavy cooler generally placed on the floor. Its function was to rinse glasses and cool wine bottles. In the 18th century, wine glasses were not set on the table, but brought to each diner by a servant. When empty they were rinsed with water from the fountain, with the dirty water discarded into the cistern, and refilled from the wine bottles chilling in the cooler.

Design & Designing

With its elaborate flowing curves and massive sculptural decoration, the set is designed to be seen as a unit and create a strong visual impact. The swelling body of this handsome urn-shaped fountain, with its gadrooning (or fluting) and rich ornament, exemplifies the grandeur and drama of the Baroque style. The dolphin has long been associated with water, and is used here to form the spout of the tap. The bold lion head finial is a further statement of ownership.

This wine fountain is from a set of silver for serving wine. The set also includes a cistern and cooler. It would have been arranged in tiers on a sideboard in the dining room, with the large and heavy cooler generally placed on the floor. Its function was to rinse glasses and cool wine bottles. In the 18th century, wine glasses were not set on the table, but brought to each diner by a servant. When empty they were rinsed with water from the fountain, with the dirty water discarded into the cistern, and refilled from the wine bottles chilling in the cooler.

Design & Designing

With its elaborate flowing curves and massive sculptural decoration, the set is designed to be seen as a unit and create a strong visual impact. The swelling body of this handsome urn-shaped fountain, with its gadrooning (or fluting) and rich ornament, exemplifies the grandeur and drama of the Baroque style. The dolphin has long been associated with water, and is used here to form the spout of the tap. The bold lion head finial is a further statement of ownership.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 3 parts.

|

| Titles |

|

| Materials and techniques | Britannia standard silver, raised, embossed, chased, engraved and cast |

| Brief description | Fountain from the Macclesfield Wine Set |

| Physical description | Britannia standard silver fountain with lid and tap, in the form of a baroque urn. The lid is surmounted by a crest in the form of a lion's head, and is decorated with bands of gadrooned ornament and palmette and shell motifs. The body swells out from the rim and is also gadrooned. Two lion's masks grapsping handles in their jaws are applied on either side at the widest point, and between them the centre of the body is decorated with an applied coat of arms and supporters (that of Thomas Parker, 1st Earl Macclesfield), surmounted with an earl's coronet. Beneath the lion's masks, which are supported on two scrolled brackets, the body tapers away, then swells out again to form the lower part of the urn. A tap with a spout in the form of a dolphin's head and handle in the form of a baroque bow is set beneath the applied coat of arms. The gadrooned stem tapers and then flares to the foot, which is decorated with embossed acanthus ornament. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Acquired with support from Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation), the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Hugh Philips Fund, and a number of private donations |

| Object history | Made for Thomas Parker, later 1st Earl of Macclesfield (born in Leek, Staffordshire, possibly 1666 and died in London, 1732), of Shirburn Castle, Oxfordshire, whose crest forms the finial of the fountain. Made in London by Anthony Nelme (active 1679-1722) Made for Thomas Parker, 1st Earl Macclesfield (1666-1732) as part of the Macclesfield Wine set. Parker was the younger son of Thomas Parker, an attorney in Leek, Staffordshire, and was called to the bar in 1691. He became a noted lawyer, his reputation in London established by his defence in the Tutchin libel case of 1704. He was appointed Lord Chief Justice in 1710 through the influence of the Duke of Somerset, and in 1718 became Lord Chancellor of England. He was a particular favourite of George I, who gave him £14,000 to mark his appointment. However, his sale of masterships in Chancery, carried out with exceptional efficiency, led to his impeachment for corruption and the end of his public life. He returned to the medieval, moated Shirburn Castle in Oxfordshire, which he appears to have modernised after its purchase in 1716. Like many of his contemporaries, he was passionately interested in science and was a member of the Royal Society and a pall bearer at Sir Isaac Newton's funeral. He was a generous supporter of the great mathematician William Jones, and created an extensive library at Shirburn. Although his fascination with science is proven, little is known of his taste in the visual arts except that he sat to Kneller. However, he cannot have been impervious to fashion, since the State Dining Room at Shirburn was remodelled with niches for plate, as at Houghton, conforming to late Baroque interior design principles, within which this set must have been displayed. It is possible that he ordered the impressive cistern, cooler and fountain when he was appointed Lord Chancellor, perhaps funded by the King's gift, and had the arms updated following his elevation to the peerage as Earl of Macclesfield in 1721. The pieces are monumental, exceptionally large and heavy, and clearly intended to be seen as an ensemble, the sculptural Baroque decoration and flowing architectural curves creating a powerfully unified design. It may be that Parker, given his respectable rather than aristocratic origins, deliberately commissioned the massively impressive set as a symbol of his newly acquired status. The fountain and the other elements of the set was supplied by the goldsmith Anthony Nelme, the son of a Hereford yeoman, was apprenticed to Richard Rowley in 1672. He was made free of the Goldsmiths' Company in 1679-80 , and went on to run one of the largest businesses of his day, specialising in grand pieces of plate for the rich such as toilet services and municipal pieces, notably maces. Despite being one of the petitioners against the alien influx in 1697, his style reflects the pervasive influence of the Huguenot silversmiths on the English craft. He was Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company twice, in 1717 and 1722. He died in 1723. His son, Francis, who was apprenticed to him, went on to make an elaborate cooler with griffin handles in 1731-2 for the Duke of Buccleuch. Historical significance: This unique set of silver for serving wine, fountain, cistern and cooler, is the ultimate expression of Baroque taste and extravagance, chosen by a newly-ennobled politician as a symbol of his new status at the peak of English society. Massive theatrical silver displayed in the dining room was not new - the silver-laden buffet was a familiar feature from the Middle Ages onwards - but ensembles of silver on this scale and in a matching design took the concept to greater heights. The Macclesfield set, unsurpassed in that all three elements survive, was until its arrival in the Museum, preserved by the family for whom it was made, unrecorded and unseen in a moated castle in Oxfordshire. The existence of a complete ensemble of fountain, cistern and cooler is uniquely important. Some six sets of fountains and cisterns alone remain in this country, either in private hands or belonging to the National Trust, for example the Thomas Farrer set of 1728-9 made for the Marquis of Exeter at Burghley. English silver on this scale must now be sought in Russia, where there are four such coolers in the Hermitage, by Philip Rollos (1705), Louis Mettayer (1712), Paul de Lamerie (1726) and Charles Kandler (1734), the latter the largest known, weighing over 7,200 ounces and with a capacity of 60 gallons. The Macclesfield silver forms the only known matching group, on a par with that issued to the Earl of Marlborough in 1701 as Ambassador to the States General, but of which only one element survives. |

| Historical context | Throughout Europe, matching sets of silver for wine are a vivid illustration of a particular facet of social convention reserved for the very wealthy. Silver coolers were familiar from the 16th century in England. One can be seen in Houckgeest's painting of Charles I and Henrietta Maria dining in public in 1635, although none survive before the 1670s. They continued to be used after the Restoration. However, between the 1670s and the 1760s, a new feature dominated the dining rooms of the seriously rich and fashionable in London, Paris, Brussels and Hanover, the display of a heavy and handsome silver fountain and basin placed on a marble-topped table, usually set in an alcove. In the grandest households, the matching but much larger silver wine cooler would stand beneath the table. William Kent's design for the Marble Parlour at Houghton Hall of 1728 and the spectacular arrangement of silver in the Rittersaal of the Berlin Schloss of around 1708 engraved by Martin Engelbrecht illustrate the point. The practical function of the set was to serve wine, rinse glasses and cool wine bottles (the 18th-century equivalent of the refrigerator and dishwasher). In the early 18th century,wine glasses were not set on the table, but brought to each diner by a servant, drained and removed for washing. Water was drawn from the fountain, the glass swilled into the cistern and refilled with wine from bottles chilling in the cooler beneath. However, these pieces were also essentially for conspicuous display and an expression of the taste of the owner. This was also by far the costliest purchase a noble patron could make. A coach could be expected to cost between £60 and £120, and a Kneller full-length portrait about £35. These pieces, at over 2,200 ounces, costing around 12 shillings per ounce including fashion would have amounted to £1,220. This was the price paid by the Jewel House for a cooler ‘curiously Enchaced' in 1720. Such a commission gave the goldsmith an opportunity to design pieces of exceptional grandeur and ambition, embellished with the owner's heraldry. Ambassadors were issued with these massive adjuncts to state dining, as was the Speaker of the House of Commons. The 1721 Jewel House inventory lists one smaller "fountain and washer" in store at 454 ounces. A late and rare survivor is the Thomas Heming cooler of 1770 made for Speaker Cust at Belton House. By the mid-18th century, dining customs had changed. Grand silver was now to be found on the table rather than the buffet and a developing sense of wine connoisseurship was reflected in the wine cooler for a single bottle. Glass pantries with running water were near at hand so the fountain, cistern and cooler ceased to be either fashionable or useful. Most, representing a significant weight in bullion, were inevitably melted down. At least seven coolers listed in the Duke of Portland's inventories were either sold or melted, and William III had four of over 1000 ounces each made after 1689, none of which survive. The result is that even sets of cisterns and fountains are now rare and there is no other complete set recorded (see N.M. Penzer The Great Wine Coolers, Apollo, 1957). |

| Summary | Object Type This wine fountain is from a set of silver for serving wine. The set also includes a cistern and cooler. It would have been arranged in tiers on a sideboard in the dining room, with the large and heavy cooler generally placed on the floor. Its function was to rinse glasses and cool wine bottles. In the 18th century, wine glasses were not set on the table, but brought to each diner by a servant. When empty they were rinsed with water from the fountain, with the dirty water discarded into the cistern, and refilled from the wine bottles chilling in the cooler. Design & Designing With its elaborate flowing curves and massive sculptural decoration, the set is designed to be seen as a unit and create a strong visual impact. The swelling body of this handsome urn-shaped fountain, with its gadrooning (or fluting) and rich ornament, exemplifies the grandeur and drama of the Baroque style. The dolphin has long been associated with water, and is used here to form the spout of the tap. The bold lion head finial is a further statement of ownership. |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.25:1 to 3-1998 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 8, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest