Altarpiece

ca. 1350-75 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

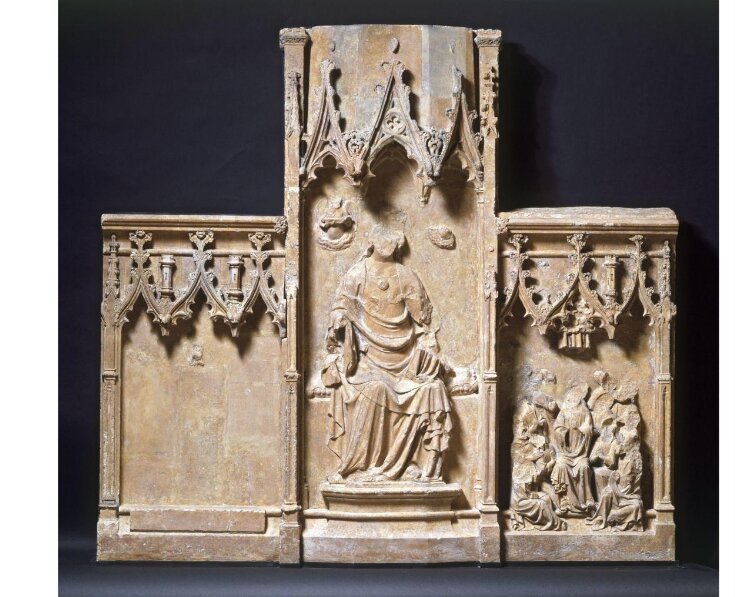

The damaged state of this altarpiece reflects the religious upheavals of 16th century England, when many sculptures and images were destroyed during the Reformation. The blank area to the left originally showed the Adoration of the Kings. On the right are the remains of the Ascension of Christ, as indicated by the toga and legs under the arch.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 3 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Carved limestone (Caen stone), with traces of paint |

| Brief description | Limestone altarpiece depicting the Virgin with Christ Child, perhaps made in London, ca. 1350-75 |

| Physical description | Three-panelled altarpiece, each panel a rectangle |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This altarpiece was once the focal point for church-goers to the parish church of St. Mary's, Sutton Valence in Kent, and depicts, as it name suggests, a series of scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary. The altarpiece is divided into three panels. The central panel, which stands higher than the other two, shows the Virgin seated on a cushion on a bench and the figure of the Christ Child, most of whom has been knocked off, standing on her knee. Angels, floating in clouds, are either side of the Virgin's head. The Virgin herself appears to have been crowned, and in keeping with the artistic conventions of the day, is represented as resembling a medieval queen - the stock contemporary image of female power, called upon by artists when a figure of a Mary, a female saint or an effigy of a deceased queen was required. The crown was an instantly recognizable symbol of earthly power and was used by medieval craftsmen (and surely women too) or 'artists' as we call them today to imply strength, both good and bad; the contemporary trappings of a stereotypical medieval queen were often roped into service when in fact the opposite virtues were being represented: those of humility, quiet suffering, patience, as opposed to the regal secular strength, the political sway and influence enjoyed by a medieval queen. Then again, most historians have seriously underestimated medieval women in the Middle Ages, and the roles they played, the contributions they made, the power they wielded, imagining them to have been powerless, miserable things at the beck and call of their menfolk; the reality was very different, and the implications of this misconception need to be considered for a fuller understanding of how the Virgin was perceived by medieval Christians. Given that women in medieval times were as gutsy and determined as men, so it was so contradictory to show the mother of the saviour of mankind as a powerful woman. The right-hand panel shows the Ascension of Christ, while the blank panel on the left almost certainly depicted the Adoration of the Magi, but the object has been seriously defaced, while the blank block at the bottom of the panel is a restoration. All three panels are crowned by canopies, giving the impression of a gothic architectural setting, each comprising three crocketed finials with hexagonal battlemented towers between. The altarpiece originally was made up of five panels, and would have represented the Five Joys of the Virgin. This was a popular subject for English sculptors, and it is commonly the theme of English alabaster altarpieces of the same period and of the century and a half after. Indeed, the technique of carving in high-relief is not so very different to that used by the alabastermen of the English Midlands, although their work was rarely as finished as that here. Likewise, the system of 'comic-book' style story-telling to relate a story is the same as that of alabaster altarpiece panels. By the time this altarpiece had been produced, the Virgin was enormously revered, hving incresed in popularity as a object of devotion and source of comfort and hope in her own right since the early years of the 14th century (at about the time when the status of women began to slowly decline). The so-called Sutton Valence altarpiece is made of limestone, a stone mainly composed of calcium carbonate (calcite: really a form of marble), much of it sedimentary, which though harder, heavier and less porous than gypsum alabaster (hydrous sulphate carbonate), was favoured by medieval sculptors for the same reasons: it was stable, could be polished, drilled and was ideal for detailed work. Some limestones are richly coloured. In England, for instance, is found the 'marbles' of the Isle of Purbeck in Somerset, which in its darker forms was favoured for column shafts in cathedrals. Since limestone was easily available in large blocks, it found favour with masons working on the decoration of churches and with sculptors producing objects of about the size of the Sutton Valence altarpiece. This piece was made from an imported variety of buff-coloured limestone called Caen stone quarried in Caen in Normandy, and much used for architecture and sculpture in England and Normandy during the Middle Ages since it was the finest limestone produced in France being fine-grained and is relatively easy to carve. Caen stone was revived as a sculptor's medium in the 19th century. But of course most medieval sculpture has been denuded of its original finish, and the Sutton Valence altarpiece, as was the norm, was once painted, for tiny traces of bright polychromy remain in places, including, interestingly, a white and chalk ground used as an undercoat. The whole object has been badly damaged. The Reformation is largely to blame, the ruthlessness of which in England in terms of image-breaking far exceeded that of any where on the Continent. Mobs directed their anger at 'idols' just like this. We can be sure that it was the Reformation that was the cause of this greivous mutilation since the tell-tale signs are there: the heads have all been knocked off. And yet, further damage was inflicted in the 19th century when it was removed from the church in the 1820s and dismantled. After 1828 it was built into the garden of no. 7, High Street, Maidstone, where it remained until 1921, in which year it was bought by the V&A. |

| Historical context | Medieval Europe was a highly visual society and sculpture was produced in enormous quantities to feed, assist and brighten the other great theme of the age, Christian worship. The majority of fine art was produced not 'for art's sake' but, ostensibly at least, to aid, encourage and assist prayer, to inform and educate worshippers, and to encourage. By the 14th century parish churches in England were filled to bursting with religious sculptures, saints' relics, tombs of local worthies, emblazoned with their arms, heraldic banners above, and a host of other paraphenalia, offerings and nick-nackery associated with Chrisitian and aristocratic life. The most prestigious (and most expensive) place for a nobleman or woman to be interred and have their effigy installed was beside the altar, a flat-topped, block-shaped table at which services were performed and prayers directed. The altar was the focal point of church-going activity, and on top of it was placed a sculpted altarpiece, carved in wood or stone and decorated with paint and gilding. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | The damaged state of this altarpiece reflects the religious upheavals of 16th century England, when many sculptures and images were destroyed during the Reformation. The blank area to the left originally showed the Adoration of the Kings. On the right are the remains of the Ascension of Christ, as indicated by the toga and legs under the arch. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.58:1-1921 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 17, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest