Mirror Case

ca. 1850 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

From the fifteenth century onward, lacquer objects – including book bindings, pen cases, boxes, Qur’an stands, and mirrors such as this one – gained popularity in Iran, peaking in production during the nineteenth century, with the Qajar dynasty (1797-1924). The vast increase in production across a variety of objects resulted in a considerable decline in quality; however, fine specimens continued to be done by certain artists in the cities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran. Much lacquerware during the Qajar period was also influenced by the increasing import of European artefacts, resulting in a distinctive Europeanization of designs and motifs. Lacquer production continued in Iran until 1924, when the Qajar dynasty was overthrown, after which point its production became determinably unfashionable.

Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.”

Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirror cases with closing shutters, such as this one, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe.

Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.”

Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirror cases with closing shutters, such as this one, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Papier-mache, painted and lacquered. |

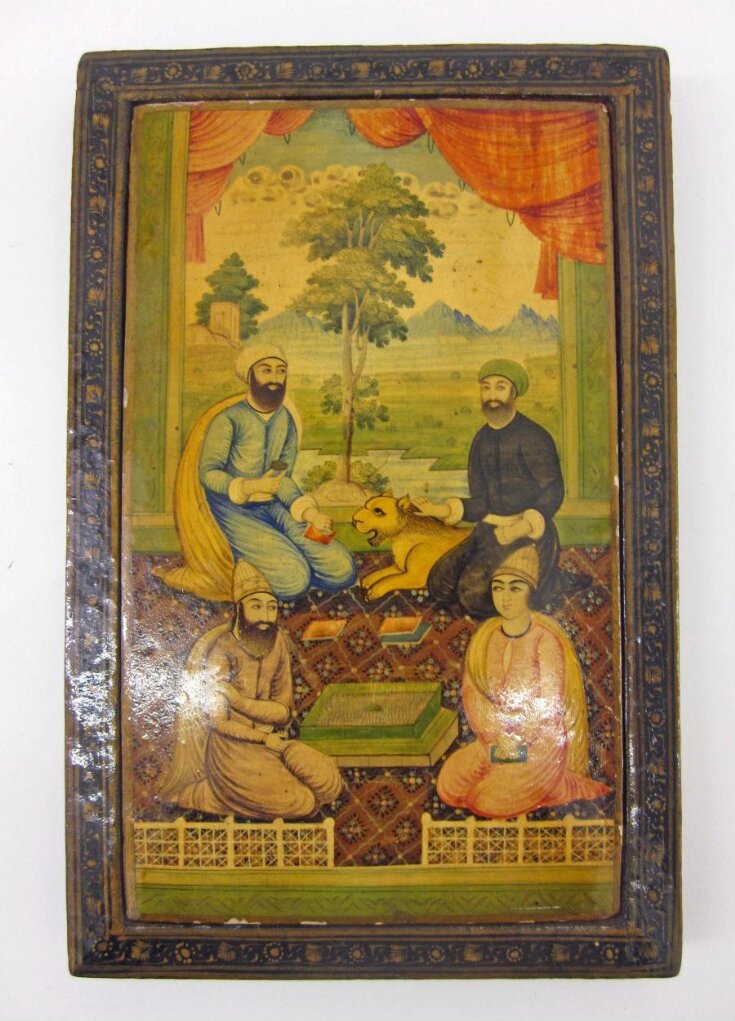

| Brief description | Mirror case with lid, depicting four seated learned men, Iran, Qajar period, ca. 1850 |

| Physical description | Rectangular shaped mirror case, painted and lacquered, depicting four kneeling men (three elderly bearded men and one youth) with books, seated around a fountain upon a carpeted, open terrace over looking a hilly landscape; one of the men strokes a seated lion. On the reverse of the case, four elder men kneel in a similar setting, each holding a book. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Production type | Unique |

| Gallery label | Both sides of this beautifully painted mirror case show groups of saints or Sufi sages gathered in conversation around a fountain. Through the open doorway of the room we see a very European landscape.

MIRROR CASE AND COVER

Iran, 19th century

Papier mache

929&A-1853(5 June 2000) |

| Object history | This object was purchased for 15 shillings in 1853. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | From the fifteenth century onward, lacquer objects – including book bindings, pen cases, boxes, Qur’an stands, and mirrors such as this one – gained popularity in Iran, peaking in production during the nineteenth century, with the Qajar dynasty (1797-1924). The vast increase in production across a variety of objects resulted in a considerable decline in quality; however, fine specimens continued to be done by certain artists in the cities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran. Much lacquerware during the Qajar period was also influenced by the increasing import of European artefacts, resulting in a distinctive Europeanization of designs and motifs. Lacquer production continued in Iran until 1924, when the Qajar dynasty was overthrown, after which point its production became determinably unfashionable. Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.” Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirror cases with closing shutters, such as this one, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 929-1853 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 16, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest