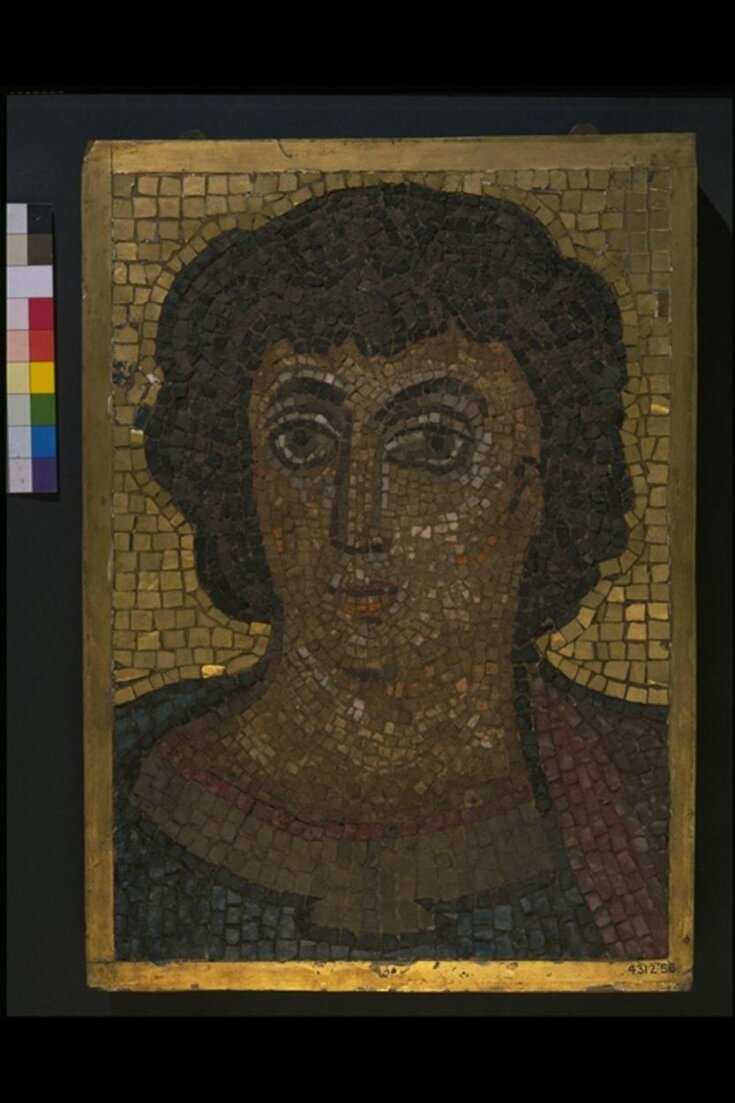

Mosaic Head

ca. 545 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Decorating floors with mosaic patterns and images was a well-established Roman tradition; however Byzantine craftsmen adapted the technique to reach new levels of opulence on walls and ceilings. This early depiction of Christ shows a young man, without the beard with which he is depicted later.

This head was purchased in Italy in 1856 by John Charles Robinson as a 'fragment of an ancient wall mosaic. Roman'. This is a very accurate summary of the object - a fragment of Roman mosaic. The face has been heavily and crudely reconstructed, probably in the 19th century. The rather flat and poorly executed blue tunic and red mantle are a 19th century attempt at 'filling in the gaps', to give the mosaic an appearance of completeness. Further to this, Christ's right eye has also been clumsily remade; so has the nose. The mouth has been partly reconstructed but not so quite so badly, and yet it lacks the definition we would expect of a late antique mosaic portrait.

Christ's flesh, however, and his hair and his left eye are clearly original, and of a superior level of workmanship to the rest of the piece. This head was previously considered to be a 5th century head of a Saint from the church of St Ambrogio in Milan, but it is now identified as being from San Michele in Africisco at Ravenna, wherein are a series of splendid glittering late Roman mosaics.

This head was purchased in Italy in 1856 by John Charles Robinson as a 'fragment of an ancient wall mosaic. Roman'. This is a very accurate summary of the object - a fragment of Roman mosaic. The face has been heavily and crudely reconstructed, probably in the 19th century. The rather flat and poorly executed blue tunic and red mantle are a 19th century attempt at 'filling in the gaps', to give the mosaic an appearance of completeness. Further to this, Christ's right eye has also been clumsily remade; so has the nose. The mouth has been partly reconstructed but not so quite so badly, and yet it lacks the definition we would expect of a late antique mosaic portrait.

Christ's flesh, however, and his hair and his left eye are clearly original, and of a superior level of workmanship to the rest of the piece. This head was previously considered to be a 5th century head of a Saint from the church of St Ambrogio in Milan, but it is now identified as being from San Michele in Africisco at Ravenna, wherein are a series of splendid glittering late Roman mosaics.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Glass and gold mosaic set in lime plaster in a wooden frame |

| Brief description | Mosaic head set in plaster lime of Christ as a young man, from the Apse of San Michele in Africisco, Ravenna, dedicated on 7th May 545 |

| Physical description | Portion of wall mosaic, heavily restored and reworked, showing the head of a youthful Christ. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This head was purchased in Italy in 1856 by John Charles Robinson as a 'fragment of an ancient wall mosaic. Roman'. The face has been heavily and crudely reconstructed, probably in the 19th century. The unattractive gold-glass field against which Christ's head is placed is no older than the 19th century. The rather flat and poorly executed blue tunic and red mantle are a 19th century attempt at 'filling in the gaps', to give the mosaic an appearance of completeness. Further to this, Christ's right eye has also been clumsily remade; so has the nose. The mouth has been partly reconstructed but not quite so badly, and yet it lacks the definition we would expect of a late antique mosaic portrait. Christ's flesh, however, and his hair and his left eye are clearly original, and of a superior level of workmanship to the rest of the piece. This head was previously considered to be a 5th century head of a saint from the church of St Ambrogio in Milan, a church founded 379-386. In 1988 the head was convincingly identified as in fact being, despite suffering so much at the hands of clumsy restorers in the employ of dealers, a head of Christ as a young man from the apse of San Michele in Africisco at Ravenna, wherein are a series of splendid glittering late Roman mosaics. In 1805 the church was closed and partially turned into a fish-market. Having been sold and now in private hands, the owner sold the mosaics of the apse and the triumphal arch in 1842 to an agent of the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. This vandalism was coordinated by a dealer in Venice, and despite protests by the local population, were taken down and removed to Venice in about 1844. A year later they were still in Venice, where they were badly damaged by a bomb blast. In 1850-1 they were crated up and packed off to Berlin by the notorious restorer Giovanni Moro. These crates remained unopened until 1875, when they were finally examined, by which time they had deteriorated badly. The crumbling mosaics were sent back again to Moro for 'restoration', which he clearly did badly, and in 1878 locked away in storage. In 1900 they were again worked on and were not set out on display for another four years. In the Second World War they suffered still further damage and were majorly conserved yet again in the 1950s. But the mosaics appear to have been in bad shape even before Moro got his hands on them. He probably salvaged what fragments and scraps he considered usable and filled in the rest with his own work. According to Andreescu-Treadgold, the V&A Christ head, along with two heads of the archangels Michael and Gabriel in the Museo Provinciale at Torcello and possibly an angel in the Hermitage, are the only pieces of the San Michele apse masterpieces. The present mosaic, being acquired only twelve years after their removal, would have escaped the fate of the mosaics sent north to Prussia, as well as the majority of the crooked and unscrupulous restorations by Moro and others. To be certain, there is a skeleton of genuine Roman Ravenna mosaic work to this saintly head; but it is like looking at a stunning landscape through thick fog - the image, the majesty, the high quality of craftsmanship of the Ravenna mosaics is visible, but seriously distorted, blurred away by brutal 19th century reworkings. Nonetheless, the nagging possibility remains that some of the worst restorations are more recent than 19th century: is the gold surround of the 1800s? The halo around Christ's head is gone (for examples of haloes about Christ's head at Ravenna see G. Bovini and M. Pierpaoli, 'Ravenna: Treasures of Light', Ravenna, 1991, plates 58 and 60). We know from a drawing made of the mosaics before their removal that the original ensemble consisted of a standing figure Christ between archangels in the conch: here then is what remains of Christ. |

| Historical context | In 404 Ravenna had become the capital of the Roman Empire in the west, after Rome had been abandoned as captial by the Emperor Honorius two years earlier. Ravenna suffered a severe period of decline after the end of the Rome era, but in its heyday was a thriving and well-fortified city - hence the stunning grandeur of these mosaics. Ravenna rose again when Theodoric the Arian, King of the Ostrogoths, captured it in 493 and established himself and his five successors there, until in 540 Belisarius, the Emperor Justinian, reclaimed the city for the Roman Empire - this time for the surviving eastern Empire - Byzantium - and it was during this period of Justinian rule that the mosaics were erected. In one, Justinian himself is represented as something between an Orthodox medieval king and an old-fashioned pagan Roman emperor, with a twist of influence from Asia Minor. Justinian valued Ravenna greatly and was keen to make it appear as impressive as he could, which is why many of the buildings around the city 'show a markedly oriental influence' (G. Bovini and M. Pierpaoli, 'Ravenna: Treasures of Light', Ravenna, 1991, p. 27), straight from the Byzantine east over which Justinian presided. Mosaic was the best means of expressing Christian faith and its miracles through a filter of Imperial Roman splendour, by virtue of the preciousness and richness of the materials used - coloured cubes of glass amid pieces of mother of pearl, gold, marble inlay and stucco adornment - to capture a brilliance and power, both of Christ and Roman power, that never fades with age, but retains its ability to inspire awe, reverence and respect for all time. The images are both stylized and realistic, expressing the earthly power and very real power of Justinian going hand in hand with the ethereal majesty of God and Christianity. |

| Production | Previously considered to be the head of a saint from the church of St. Ambrogio, Milan |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Decorating floors with mosaic patterns and images was a well-established Roman tradition; however Byzantine craftsmen adapted the technique to reach new levels of opulence on walls and ceilings. This early depiction of Christ shows a young man, without the beard with which he is depicted later. This head was purchased in Italy in 1856 by John Charles Robinson as a 'fragment of an ancient wall mosaic. Roman'. This is a very accurate summary of the object - a fragment of Roman mosaic. The face has been heavily and crudely reconstructed, probably in the 19th century. The rather flat and poorly executed blue tunic and red mantle are a 19th century attempt at 'filling in the gaps', to give the mosaic an appearance of completeness. Further to this, Christ's right eye has also been clumsily remade; so has the nose. The mouth has been partly reconstructed but not so quite so badly, and yet it lacks the definition we would expect of a late antique mosaic portrait. Christ's flesh, however, and his hair and his left eye are clearly original, and of a superior level of workmanship to the rest of the piece. This head was previously considered to be a 5th century head of a Saint from the church of St Ambrogio in Milan, but it is now identified as being from San Michele in Africisco at Ravenna, wherein are a series of splendid glittering late Roman mosaics. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 4312-1856 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 6, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest