Sarcophagus part of the Beata Chiara Ubaldini

Sarcophagus Front

ca. 1325 (made)

ca. 1325 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This relief panel was originally part of the tomb shrine of the Blessed Chiara Ubaldini, a member of the order of Poor Clares, the female wing of the Franciscan Order. Chiara was abbess of their convent at Santa Maria di Monticelli in Florence during the 1200s or early 1300s. Chiara was popularly believed to have been a saint, and miracles had occurred at her tomb. This slab was part of a monument erected to serve as a focus for her developing cult. The original appearance of this monument is now difficult to reconstruct, but it may have taken the form of a wall tomb with an altar attached. The inscription makes punning use of Chiara's name, which means 'clear' or 'bright' to suggest that she was a shining example of the Poor Clares' way of life.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Sarcophagus part of the Beata Chiara Ubaldini (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Marble, carved in relief |

| Brief description | Panel, marble, carved in relief, front of a sarcophagus, of the Beata Chiara Ubaldini, in S Maria di Monticelli in Florence, Italy (Florence), about 1325 |

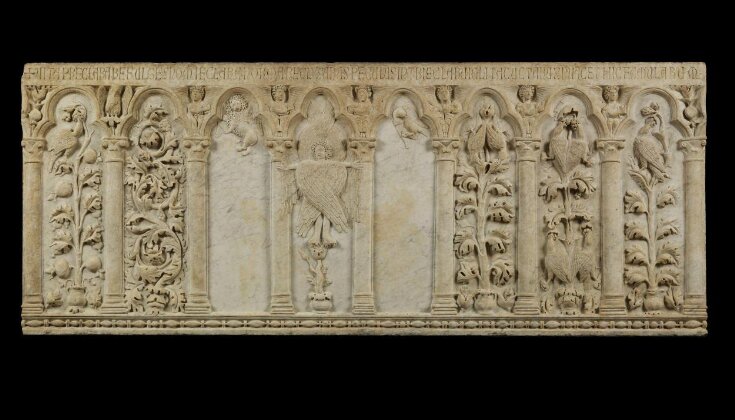

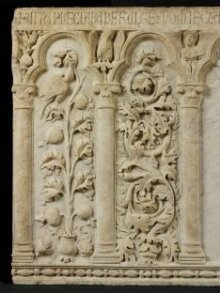

| Physical description | A marble slab, carved in relief with a colonnade of six trefoil headed arches, supported on Ionic columns. The outer six compartments contain foliage sprouting from vases, some inhabited by birds. The fourth compartment from the left contains a seraph rendered frontally, standing on a foliate branch with arms outspread. To either side appear the Lion of St Mark and the Eagle of St John. Above runs an inscription. Below is a bead and reel moulding. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 'VITA PRECLARA . REFVLGE[n]S NOMI[n]E CLARA . NORMA RECLVSARV[m] . SPECVLV[m] SIN[e] T[ur]BI[n]E CLARV[m] . I[n]CLITA CV[n]CTARV[m] XR[ist]I IACET HIC FAMVLARVUM' (The inscription appears in a single line along the top of the slab above the arcades. The abbreviations have been expanded in the transcription within square brackets. There is a mistake in the inscription, which places a contraction mark above the start of the word 'SPECULU[m]' where there is in fact no contraction.)

|

| Object history | Museum records indicate that the relief was acquired in Florence, in 1882, by J.C. Robinson, although they do not specify from whom he bought it. He wrongly believed it to be the sarcophagus of Saint Clare of Assisi. The true provenance of the relief was only recognised in 1949, when it was published by John Pope-Hennessy. The life of Chiara Ubaldini is still somewhat unclear. Although fifteenth and sixteenth century accounts of her life and miracles describe her as the second abbess of the convent, dying some time in the 1260s or 1270s, it has also been argued that in fact she should be regarded as having been abbess only in the fourteenth century, dying some time after 1327, when a 'Sister Chiara' is recorded as abbess of the community. In either case, it is clear from stylistic comparisons that the relief slab dates to the 1320s. One of the community's earliest historians, the sixteenth century priest Fra Mariano di Ognissanti, records that some time after Chiara's death, the nuns moved her tomb from inside the cloister to a wall adjoining the external church to permit greater access to the tomb, as a result of the miracles that were occuring there. It is therefore possible either that the relief was created at the time of the moving of the tomb, or that it dates from the time of the death of the Beata, if we accept that she lived in the fourteenth century, rather than the thirteenth. The moving and modification of the tombs of those who were popularly believed to be saints is documented in other cases. The Beata Margherita of Cortona was initially interred in a shrine which was freestanding, and which was enclosed by an iron grille. In the fourteenth century, an elaborate wall tomb with an altar attached was created in order to further bolster her cult. The V&A relief did not remain in its original context for long. The thirteenth-century church of the Poor Clares outside the Porta Romana was demolished in 1527, when the convent was demolished by the Florentine state as part of the rebuilding of the city's defensive walls. The Franciscan church of S. Croce temporarily housed some of the community's possessions, including the tomb and remains of Beata Chiara. In 1534, the Poor Clares moved into a new home within the city in Via de' Malcontenti, at which time it was discovered that although the Beata's tomb had survived, the body itself was missing. It was this re-erected and empty monument which was seen and described by the antiquarian historians on whom we now rely for information on the early history of the V&A slab. During the Napoleonic period, in 1808, the convent was suppressed, and it was probably at this time that the V&A relief became a free-standing object. Nothing is known of its history between this time and the acquisition of the piece towards the end of the century. Historical significance: The tombs of those popularly venerated as saints were potent sites of religious devotion in this period. Such saints and beate often arose amongst the mendicant orders. This piece is also a significant example of the kinds of art which were produced for female religious houses. |

| Historical context | The original form of the monument of which this relief formed a part is a matter for debate. Only one historical commentator describes the monument as it must originally have been - the early sixteenth-century writer Fra Mariano di Ognissanti, whose description was published in the 1700s by the antiquarian Richa. Fra Mariano uses the term 'arca' to describe the tomb monument. There are also several descriptions of the monument as it was reconstructed in the new convent of the Poor Clares in the Via de' Malcontenti, Florence, dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. From these descriptions, it is clear that some of the original decoration is now missing, in the form of men and women dressed as penitents. John Pope-Hennessy suggested that this decoration was from the side panels of the tomb, but this seems to be ruled out by the description of Follini-Rastrelli of 1794, which specifies that the carving of the monument was 'on the front' ('nel davanzati'). Jeryldene M. Wood, following Moskowitz's definition of an 'arca' as a free-standing monument, has envisaged the V&A slab as part of a large ensemble, decorated on all four sides, and with the tomb chest perhaps raised up on pillars in the manner of the Arca di San Pietro Martire in Sant' Eustorgio, Milan (1339). She gets around the difficulty of Fra Mariano's description of the monument having been attached to a wall by making the unconvincing suggestion that the tomb could have been placed in an opening in the wall, accessible from both sides. Moskowitz's definition of an 'arca' as an exclusively free-standing genre of tomb is in fact highly debateable, and all the evidence we have suggests that the tomb monument of Beata Chiara was a wall-mounted monument, with a strongly frontal aspect. Julian Gardner has made the suggestion that the V&A panel is in fact the front part of the High Altar block, and that the Beata would have been interred, following an established Franciscan practice, beneath the high altar. This argument has many merits - it envisages a much smaller monument, of which the V&A panel would have formed the major part. It also takes into account the similarity of form between the decoration of the V&A slab and altar blocks of this date - for example, the use of a very similar trefoil headed arcade on the altar attached to the tomb of Cardinal Giovanni Gaetano Orsini in the Lower Church of San Francesco, Assisi (ca. 1294). The iconography of the V&A piece, unusual in not featuring any reference to the Beata's life, also becomes more explicable in this eucharistic context. The prominent seraph, located under one of the middle arcades, has often been interpreted as a reference to the stigmata of St Francis. But given that the seraph does not bear the marks of the stigmata, he may well be intended to be read more generally as a eucharistic sign. The 'S' symbols visible on some of the books held by the angels may refer to the "sanctus, sanctus, sanctus" sung by those surrounding the throne of God in the book of Revelation. The foliage inhabited by birds pecking at fruit might be read as a reference to Jesus' claim to be the True Vine (John 15:1). Gardner also points out the similarity in size between the V&A panel and the altarpiece which we know was on the high altar in S. Maria in Monticelli (Florence, Accademia, 1383). However, this hypothesis also leaves several outstanding problems. Firstly, the prominent inscription on the V&A slab, if it is accepted as an altar, starts to read as an altar titulus, but if so, then it is a very odd one, partly because of its obvious tomb references, and partly because an altar could not be dedicated to a Beata (although there is some evidence that this occasionally happened). Secondly, it leaves open the question of the missing imagery. This is described as having represented men and women clothed as penitents. It presumably also included the evangelist symbols for Matthew and Luke. Pope-Hennessy suggested that this imagery could have been placed on the sides of the chest, but as noted above, a 1794 description specifies that it was 'on the front'. If this source is to be trusted, then the other option would be to hypothesise a sculpted lid, such as are often seen on other 'arca'-type tombs, such as Goro di Gregorio's Arca di San Cerbone of ca. 1330. Given all of this evidence, two hypotheses appear most credible: either Gardner's suggestion that the V&A panel was part of an altar, where the missing imagery would have to be accommodated at the sides, or that the V&A panel was indeed as it was always later described, a sarcophagus. This sarcophagus was probably wall mounted, given Fra Mariano's specification of a wall location, and the fact that when the sarcophagus was opened in 1459, it was replaced 'in a high place'. If this was the case, then the tomb would have resembled that of the Beata Margherita in Cortona, although the Monticelli tomb may well not have been so grand, lacking for example the architectural canopy of the Margherita monument. The Monticelli tomb may well also have been linked to an altar. This was certainly the case for other Beate. This would explain the eucharistic overtones of the sarcophagus imagery. The missing imagery may have appeared on the sides of the sarcophagus, but probably featured on a sculpted lid. There are traces on the sides and back of the V&A relief of fixings which would have held both side panels and a lidl in place, although the date of these marks is difficult to ascertain. |

| Production | The exact correspondence between the inscription on this object and the inscription recorded in various antiquarian sources as having been on the sarcophagus of the Beata Chiara Ubaldini in the church of Santa Maria di Monticelli in Florence means that we can be sure of the original provenance of this piece. However, stylistic evidence conclusively demonstrates that this slab was not created at the time of the Beata Chiara's death as described in hagiographical accounts. John Pope-Hennessy's comparisons with tomb monuments in Florence of the 1320s, such as the Baroncelli monument in the church of Santa Croce, remain convincing. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This relief panel was originally part of the tomb shrine of the Blessed Chiara Ubaldini, a member of the order of Poor Clares, the female wing of the Franciscan Order. Chiara was abbess of their convent at Santa Maria di Monticelli in Florence during the 1200s or early 1300s. Chiara was popularly believed to have been a saint, and miracles had occurred at her tomb. This slab was part of a monument erected to serve as a focus for her developing cult. The original appearance of this monument is now difficult to reconstruct, but it may have taken the form of a wall tomb with an altar attached. The inscription makes punning use of Chiara's name, which means 'clear' or 'bright' to suggest that she was a shining example of the Poor Clares' way of life. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 46-1882 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 27, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest