Candlestand

1400-1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

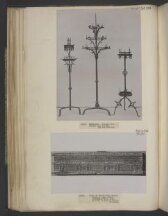

This large candlestand probably stood in a church choir, or before a tomb. The revolving rings that held the candles meant they could be added and snuffed out more easily. Similar examples from Belgium (Tournai, Ypres and Lierre) dating from 1490s - 1510s are illustrated in D'Allemagne, Histoire du Luminaire, pp.161-2.

The use of lighted candles as a sign of respect or devotion towards gods, the dead or the emperor in Roman times was transferred to rituals of Christian worship. In the Christian church, candles were carried individually in processions and set in clusters beside tombs, especially those of martyrs. Increasingly, candles became central to worship: successive popes from the ninth century onwards forbade mass to be said without light. Initially candles were placed beside the altar during mass, but from the eleventh century onwards they were placed on the altar itself. In the context of Christian writings and worship, the light of a candle had a number of symbolic associations, among them the light of divine knowledge and of life. The number of candles used could also have symbolic significance, although this significance varied across the centuries and according to local custom. Sometimes extinguishing a candle was as significant as lighting it. Prayers said during the hours of darkness and on Friday and Saturday before Easter came to be known in Latin as 'tenebrae' ('darkness') because as they were said, the candles in the choir were gradually snuffed out. This reflected not only the fact that the prayers were said at night, but also the account in the Gospel according to St Matthew of the darkness that enveloped the earth for three hours before Christ's crucifixion (Matthew 27.45).

The use of lighted candles as a sign of respect or devotion towards gods, the dead or the emperor in Roman times was transferred to rituals of Christian worship. In the Christian church, candles were carried individually in processions and set in clusters beside tombs, especially those of martyrs. Increasingly, candles became central to worship: successive popes from the ninth century onwards forbade mass to be said without light. Initially candles were placed beside the altar during mass, but from the eleventh century onwards they were placed on the altar itself. In the context of Christian writings and worship, the light of a candle had a number of symbolic associations, among them the light of divine knowledge and of life. The number of candles used could also have symbolic significance, although this significance varied across the centuries and according to local custom. Sometimes extinguishing a candle was as significant as lighting it. Prayers said during the hours of darkness and on Friday and Saturday before Easter came to be known in Latin as 'tenebrae' ('darkness') because as they were said, the candles in the choir were gradually snuffed out. This reflected not only the fact that the prayers were said at night, but also the account in the Gospel according to St Matthew of the darkness that enveloped the earth for three hours before Christ's crucifixion (Matthew 27.45).

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Ironwork |

| Brief description | Iron. France. 1400-1500. |

| Physical description | Candlestand of wrought iron. The tall stem has hexagonal and circular sections, and stands on three curved feet. It supports three revolving rings which have alternating prickets and sockets for holding candles. There are four prickets and four sockets on each ring, arranged alternately (two prickets on the middle ring are broken). Each ring is strengthened by four brackets decorated with spikes and knobs The rings have vertical grooves on their outer edge. The stem terminates upwards in a pricket and is ornamented by two rings with mouldings. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This large candlestand probably stood in a church choir, or before a tomb. The revolving rings that held the candles would have enabled these to be snuffed out more easily during the prayers known as 'tenebrae' ('darkness'), when church lights were gradually extinguished. Similar examples from Belgium (Tournai, Ypres and Lierre) dating from 1490s - 1510s are illustrated in D'Allemagne, Histoire du Luminaire, pp.161-2. |

| Historical context | The use of lighted candles in Roman times as a sign of respect or devotion towards gods, the dead or the emperor was transferred to rituals of Christian worship. In the Christian church, candles were carried individually in processions and set in clusters beside tombs, especially those of martyrs. Increasingly, candles became central to worship: successive popes from the ninth century onwards forbade mass to be said without light. Initially candles were placed beside the altar during mass, but from the eleventh century onwards they were placed on the altar itself. In the context of Christian writings and worship, the light of a candle lent itself to a number of symbolic interpretations, among them the light of divine knowledge and of life. The number of candles used could itself have symbolic significance, although this significance varied across the centuries and according to local custom. Sometimes extinguishing a candle was as significant as lighting it. Prayers said during the hours of darkness and on Friday and Saturday before Easter came to be known in Latin as 'tenebrae' ('darkness') because as they were said, the candles in the choir were gradually snuffed out. This reflected not only the fact that the prayers were said at night, but also symbolized the darkness that enveloped the earth for three hours before Christ's crucifixion, as recorded in the Gospel according to St Matthew (Matthew 27.45). |

| Summary | This large candlestand probably stood in a church choir, or before a tomb. The revolving rings that held the candles meant they could be added and snuffed out more easily. Similar examples from Belgium (Tournai, Ypres and Lierre) dating from 1490s - 1510s are illustrated in D'Allemagne, Histoire du Luminaire, pp.161-2. The use of lighted candles as a sign of respect or devotion towards gods, the dead or the emperor in Roman times was transferred to rituals of Christian worship. In the Christian church, candles were carried individually in processions and set in clusters beside tombs, especially those of martyrs. Increasingly, candles became central to worship: successive popes from the ninth century onwards forbade mass to be said without light. Initially candles were placed beside the altar during mass, but from the eleventh century onwards they were placed on the altar itself. In the context of Christian writings and worship, the light of a candle had a number of symbolic associations, among them the light of divine knowledge and of life. The number of candles used could also have symbolic significance, although this significance varied across the centuries and according to local custom. Sometimes extinguishing a candle was as significant as lighting it. Prayers said during the hours of darkness and on Friday and Saturday before Easter came to be known in Latin as 'tenebrae' ('darkness') because as they were said, the candles in the choir were gradually snuffed out. This reflected not only the fact that the prayers were said at night, but also the account in the Gospel according to St Matthew of the darkness that enveloped the earth for three hours before Christ's crucifixion (Matthew 27.45). |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 544-1895 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 30, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest